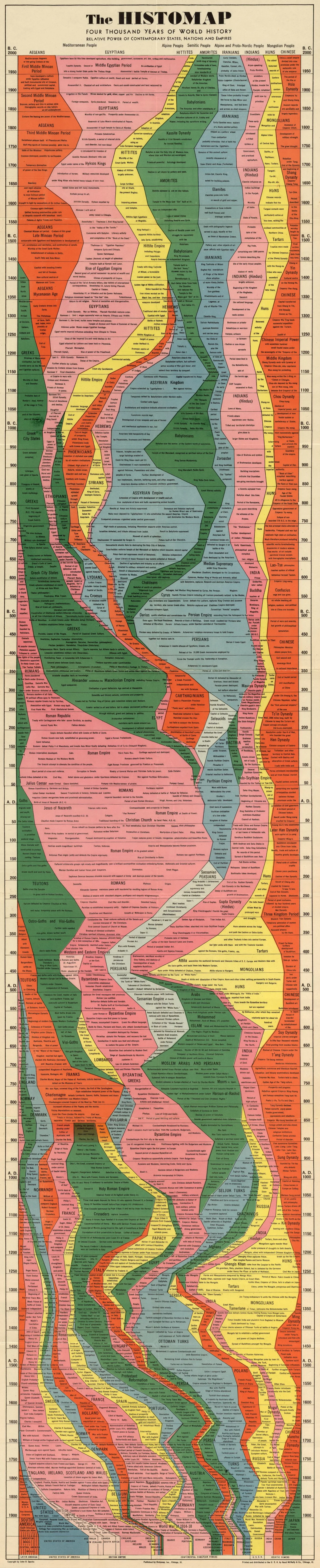

See the high-resolution version of this image by clicking here

The Rise and Fall of Civilizations, on One Epic Visual Timeline

See visuals like this from many other data creators on our Voronoi app. Download it for free on iOS or Android and discover incredible data-driven charts from a variety of trusted sources.

Key Takeaways

- The famous Histomap tries to show 4,000 years of human civilization wrapped up in one epic visual.

- Originally created in 1931 by John B. Sparks, it shows the extent of different civilizations throughout time. The wider the column, the more influence they had at that point in history.

- Being made almost a century ago, the Histomap has obvious limitations in the modern context, which are discussed below.

World history is extremely complicated and nuanced.

And yet, there is a very human desire to put all of it in one neat and tidy package—as if we can momentarily ignore what happens at the edges—disagreements, gray areas, and unresolved debates.

Creating a “single artifact” that sums up all of human history has been tried many times.

Ancient writer Eusebius had a go in the 4th century. Writer H.G. Wells tried it in 1920 with The Outline of History. More recently Yuval Noah Harari saw commercial success with Sapiens, which was framed as distilling human progress into one book.

Enter: The Histomap

Created in 1931 by John B. Sparks, Histomap is one of the world’s most famous historical visualizations.

It starts its journey 4,000 years ago in the Bronze Age, with familiar civilizations like the Egyptians, Greeks (Minoans), and Indians (Indus Valley). As you scroll through the visualization, more familiar names appear (Assyrians, Romans, Parthians, Huns, etc.) until you get to the nation states we know today.

As the reader scrolls through, you can see the rise and fall of these civilizations, imagining pivotal moments like the Battle of Thermopylae or the Battle of Waterloo. You can picture the famous figures like Augustus, Alexander, Genghis Khan, George Washington, Ashoka, or Cyrus the Great shaping world affairs.

It’s ambitious. It’s confident. It’s epic.

But is it accurate?

History is Dynamic and Always in Flux

The problem with this extremely confident take is that our understanding of history changes over time.

When Histomap was made, the world felt knowable and progress seemed inevitable. History was often told as a single, linear story driven by empires, leaders, and progress.

Over time, however, that confidence eroded.

New perspectives—from marginalized voices to systems like economics, climate, and technology—revealed history as fragmented, contested, and incomplete. We gained more data than ever before, but lost agreement on what matters most. History didn’t become messier; we simply stopped pretending it was tidy.

What’s “Wrong” With the Histomap?

Viewed in historical context, there is nothing inherently “wrong” with the Histomap.

Judged by modern standards, however, it has clear limitations.

- Civilizations are shown as clearly bounded units

Example: Rome appears to end in 476 AD, despite Roman law, culture, and institutions continuing for centuries in Byzantium and Europe. - Political power is prioritized over social influence

Example: Territorial empires dominate the chart, while the spread of religions like Buddhism or Christianity is visually secondary. - The perspective is Western-centric

Example: European timelines are detailed and continuous, while African and Indigenous American civilizations are compressed or simplified. - History is presented as linear and settled

Example: Civilizations rise and fall cleanly, leaving little room for overlap, ambiguity, or disputed transitions. - The visualization reflects 1931-era knowledge

Example: Later discoveries and reinterpretations—such as Göbekli Tepe or revised views of the Indus Valley—are not represented.

The Urge Will Endure…

Despite the aforementioned limitations above, it seems unlikely that humans will be able to resist the urge to neatly package human history in the future.

We want to understand, and seeing history as one singular narrative helps us do that—even if it’s not perfect.

And for that reason, the Histomap, along with similar attempts to codify human history and progress, will continue to endure.