Standard & Poor’s slashed the credit ratings of 112 corporations around the globe to default (D) or selective default (SD) in 2015, according to S&P Capital IQ Global Credit. The highest number of global defaults since nightmare-year 2009, when a previously unthinkable 268 companies defaulted, and not far behind the second highest default tally of 125, in 2008.

The oil & gas sector led with 29 defaulters (26% of the total). Metals, mining, and steel followed with 17 defaulters (15% of the total). The consumer products sector and the bank sectors tied for the third place, each with 13 defaulters (12% of the total).

So where are the defaulters? In Russia and Brazil? The economies of both countries have been ravaged by deep recessions and other problems. They rank high on the list but the country with most of the defaulters is… the US.

In total, 66 defaulters were US issuers, up 100% from 33 in 2014, and the highest since 2009. US defaulters accounted for 59% of the global total. Some of this dominant share of defaulters can be attributed to the size of the US economy and the enormous size of its credit market. But the US is also the epicenter of oil & gas defaults, with contagion now spreading to other sectors.

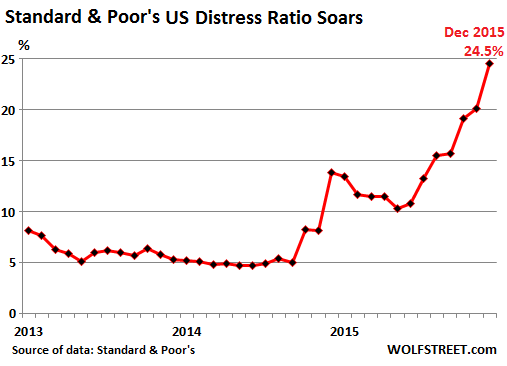

An indication of what’s coming in 2016 is the Standard & Poor’s Distress Ratio. It’s the proportion of junk-rated bonds with yields that exceed Treasury yields by at least 10% (option-adjusted spread). And this Distress Ratio soared in December to 24.5%, up from around 5% in 2014. There are now 437 bond issues tangled up in the ratio:

Of those 437 bond issues in the Distress Ratio, 127 have been issued by oil & gas companies. The metals, mining, and steel sector has 71 bond issues in the ratio. The remaining 239 issues are spread over other sectors. And a number of these distressed issuers will default down the line. So defaults in the US are likely to get even uglier in 2016.

Emerging Markets were in second place with 25 defaulters, up from 15 in 2014 and the highest since 2009, according to S&P Capital IQ Global Credit, “owing largely to a credit spillover effect of the increasingly unfavorable geopolitical climate in Brazil and Russia.” Brazil sported eight defaulters, and Russia seven, thus occupying the second and third country-rank behind the US.

In Europe, where QE and negative yields are raging, S&P downgraded 16 issuers to default, up 167% from 2014, despite the current monetary policies that should make defaults virtually impossible. The remaining 5 defaulters were spread over other developed nations (Australia, Canada, Japan, and New Zealand):

[image]https://wolfstreet.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Global-corporate-defaults-2004-2015.png[/image]

There are different reasons companies can be downgraded to D or SD. Of the 112 defaulters, 36 (or 32% of the total) undertook “distressed debt exchanges,” a favorite extortion method in the US oil & gas sector, whereby the company tells investors to swap existing bonds for new bonds with a huge haircut, or risk an even worse fate in bankruptcy court. This tool is becoming increasingly popular: in 2015, 32% of defaults were distressed debt exchanges, up from 23% in 2014.

Another 32 defaulters failed to make interest or principal payments, while 22 filed for bankruptcy. Among the remaining defaulters, 11 were the result of regulatory interventions.

Standard & Poor’s global “weakest links” – companies on the lower end of the junk-bond spectrum most in danger of defaulting – reached 195 in December, the highest since March 2010 (when there were 203), representing $234 billion in rated debt, with oil & gas in first place and financial institutions (!) in second place:

Drops in oil prices affected the profitability of oil and gas companies, where spreads have widened considerably. This spread expansion has had a spillover effect upon the broader range of speculative-grade rated firms, where spreads have widened considerably leading to increased default risk.

What’s next in the US? Standard & Poor’s upgraded 18 companies with total debt of $49 billion, but downgraded 60 companies with a breath-taking total debt of $1.3 trillion (with a T).

So 2015 ended on an ugly note. But there is still no crisis of any kind. Yes, the price of commodities has collapsed, but money is still nearly free for high-grade borrowers. Numerous governments and corporations can borrow at negative yields, thus getting paid to borrow, a central-bank engineered absurdity. And many more can borrow below the rate of inflation – i.e. for free. And yet, defaults are surging.

And it’s just the beginning.

The non-dollar world has piled on nearly $10 trillion in dollar-denominated debt, betting that the dollar would never rise, and that US interest rates would stay low. But the dollar has soared and US interest rates are rising. The last time this happened was 1997. It triggered massive currency outflows from those countries and all kinds of crises, including the big one at the time, the Asian Financial Crisis, according to the economists at National Bank of Canada, who added, “It would be foolish to rule out a similar if not a more devastating outcome.” Read… What Will Knock the Dollar off its Perch?