Submitted by Jeffrey Snider via Alhambra Investment Partners,

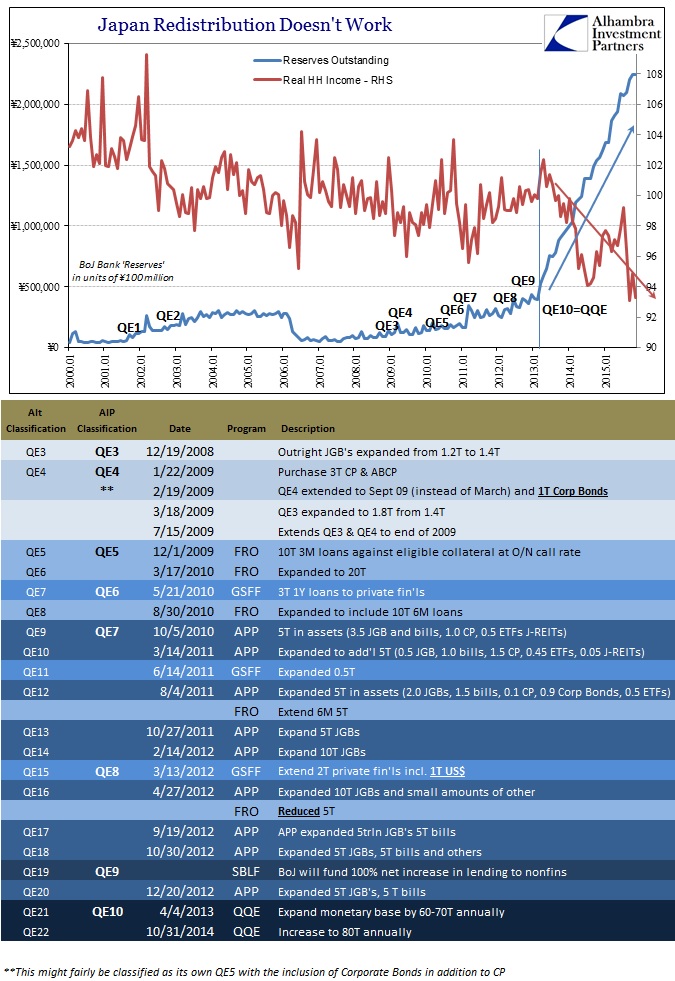

At what point do we accede back to logic and rational thought? The Bank of Japan is “forced”, not my word, to unleash negative nominal interest rates and that is taken as a positive for everyone everywhere. Such a move is, without question, an open admission that QQE failed and failed spectacularly (since it was even expanded not really that long ago). That is cause for celebration and optimism?

Bloomberg tells us that a grim January gets to now end on a high note (that was the article’s title, after all) without ever pausing to consume the fact that January was so grim to begin with because nothing central banks do actually matter beyond the very short run.

U.S. stocks joined an advance in global equities, while bonds rallied as the Bank of Japan’s unexpected monetary stimulus boosted confidence that central banks remain vigilant of slowing economic growth. The yen tumbled, while oil gained.

The story performs the usual magic trick of semantics in favor of a positive reinforcement on the central bank activity; “central banks remain vigilant”, as if vigilance is all that is required or offered. It is neither. In the Bank of Japan’s case, what was delivered was supposed to be an enormous monetary wave of such fury and power as to leave no doubt as to how this was going to end. In April 2013, BoJ officials were so confident that they even provided a timetable for its expected completion – sustainable 2% inflation by the middle of 2015 (the end of 2015 if “unforeseen” problems developed).

Because inflation is taken as a signal of a healthy economy, that was all that was thought necessary. It obviously wasn’t, since not only was there a striking and deep recession in the middle of 2014 for Japan (which was and is blamed, wrongly, on the tax alteration) the BoJ actually scaled up QQE later that year.

The initial conditions for QQE in April 2013 were questionable, but central bankers remained undeterred; going so far as to vow to keep doing QE in its last format until it worked.

Former investment-bank economists Takahide Kiuchi and Takehiro Sato, who joined the board last year, opposed today’s statement that inflation is likely to reach 2 percent in the latter half of the three-year BOJ forecast horizon, Kuroda told reporters at a press briefing today. He said he personally thinks the goal will be achieved in the 2015 fiscal year.

Kuroda said that no board member judged that additional easing was needed now, and that policy adjustments would be made if necessary. The bank will keep its stimulus until stable 2 percent gains in consumer prices are realized, he said.

Even under the expanded version of QE10 (or 11, depending on how you define and count them) it isn’t enough. If the BoJ “has” to now add negative interest rates the only way to judge all the QE’s dating back to 2001 is as total failures. But that isn’t the full weight of reckoning, either, as it is plain that the Japanese people, households, have paid a very heavy price for all of the continuous balance sheet expansion and yen debasement.

The idea of monetary intervention in this fashion is redistribution; that some economic agents will benefit at the expense of others. While that “expense” is acknowledged by the monetary central planners, they feel it necessary in order to achieve economic pump priming again. Thus, those who lose out in the initial stages of QE are expected to be eventually rewarded by the full recovery (omelets need broken eggs). Ben Bernanke was (in)famous in that respect, often talking about the woes of those savers depending upon fixed income who will be richly rewarded for their pain when his theory is proven correct.

When I was chairman, more than one legislator accused me and my colleagues on the Fed’s policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee of “throwing seniors under the bus” (to use the words of one senator) by keeping interest rates low. The legislators were concerned about retirees living off their savings and able to obtain only very low rates of return on those savings…

In recent years, several major central banks have prematurely raised interest rates, only to be forced by a worsening economy to backpedal and retract the increases. Ultimately, the best way to improve the returns attainable by savers was to do what the Fed actually did: keep rates low (closer to the low equilibrium rate), so that the economy could recover and more quickly reach the point of producing healthier investment returns.

That last paragraph is tragic in all the ways that are evident right now and suggested for the upcoming intermediate term. Savers and households (true state of the labor market) not just in Japan have been bearing this burden of redistribution for more than a decade (and almost a decade in the US and Europe) and still they are forced to ask where is the recovery to reward their dictated drain? It’s all the more distressing given that question still unresolved just as concerns turn increasingly toward the “next” downturn. Why is the economy always in the initial stages of recovery so that, years upon years later, it still cannot withstand the slightest alteration of monetary genius? It stops being redistribution and takes on the proportions of unnecessary and even criminal torture. The banks must always win so that the people might in a generation or two down the road?

This is madness, pure and simple. And it takes on just those characteristics in light of the ECB’s totally deficient experience with negative rates and QE. Consider: the BoJ is now supplementing QQE with negative rates just as the ECB has been supplementing negative rates with QE. What planet is this?

The end of QE as a monetary appeal should be heralded as a huge victory for the forces of common sense, but instead it only demands the further death of money. Not merely content to squeeze “store of value” down to its last remaining elements, central banks apparently will take the next step and make it actually painful as if it wasn’t before. There are no “high notes” to this kind of affair, only lower lows.

This is why economics is not in any way like a science, let alone an actual scientific discipline. It is the Aristotelian method of divining essence and then expecting the world to unfold according to that internal epistemology; and when it inevitably doesn’t, there is no mechanism for correction. The economist will declare in no uncertain terms that monetary policy works, and that a lot of it will undoubtedly work well. No matter how long that position remains in the negative, nothing causes feedback that dislodges the initial premise. Instead, as if to prove the anti-scientific nature of orthodox economics and especially econometrics, the economist will search high and low in everything but monetary policy for the potential answer (such is the holy grail of monetary neutrality).

In March 2015, Kuroda had already essentially dismantled QE anyway by exposing that myth.

First, the initial rounds of QE weren’t potent enough. “In order to escape from deflationary equilibrium, tremendous velocity is needed, just like when a spacecraft moves away from Earth’s strong gravitation,” Kuroda recently explained. “It requires greater power than that of a satellite that moves in a stable orbit.”

This is hysteresis, an unnecessarily complicated word that essentially means an economy cannot move without external strength of monetary policy; you have to unleash enough force to get even small rock to roll down an incline. The bigger the rock, the more force necessary to get it rolling. That was the point of the “Q” in QE. The term itself was meant to convey the supposedly objective mathematics at work, harnessed by experts displaying immense technical knowledge. That economists working in central banks could precisely measure and determine the size of the rock and the degree of the slope so that they could exactly, quantitatively calculate the exact force necessary to start the forward rolling progress. Stock prices cheered when they made the claim, and now they cheer when it is disproven?

Actually, the entire idea was disproven by time some time ago, instead stocks are nearly euphoric (even for just a day) that such was actually acknowledged by those central bankers moving on to another kind of “Q’ (and hoping you don’t notice). I wrote just last Friday:

So in broad and general terms, we find that central banks all around the world have turned to increasingly absurd ways with which to make monetary policy find their intended depth; and still they never do. The things that have happened in the past few years would have in 2006 been judged utterly insane. We may have become far too desensitized by now, but if you told Bernanke that the Bank of Japan would be buying corporate debt at negative yields, as it did just this week, and that it wasn’t so outlandish to assume that the Fed might follow, he and everyone else would have dismissed you outright as insane. It no longer is.

If this year turns out the way it is already shaping up, can you really not imagine Janet Yellen (or her successor, assuming she doesn’t survive the growing debacle) doing the same as the Bank of Japan? There has already been a steady growth of stories and rumors, all emanating carefully from that policy corridor, of intellectual flirtations with negative interest rates. Not only that, the FOMC in June 2003, just as Greenspan was achieving his “ultra-low”, ridiculed the Bank of Japan for its first two (of ten or eleven, depending on how you count) QE’s – only to follow them almost exactly just five years later.

Ten years ago, all this would have been written off as the stuff of an insane mind or conspiracist. Now, it is just normal and economists would have you think it the only option. This is inflation; true inflation. The standards of actual conduct have been so eroded and degraded as to be totally meaningless; there is nothing left for honest trade except the further death of money. What we are finding is that it is not a “clean death”, however, but a tortured journey on a winding road of further and further madness. It only ends when someone finally gets to question why an economy needs monetary policy in the first place. Can an economy really not grow without it, or central banks? If there is only increasingly absurd monetarism in our future, the answer to that most fundamental question is not all that difficult.