Wolf Richter www.wolfstreet.com

The post-February euphoria in the US bond market has been a sight to behold, stirred up by NIRP and QE in Japan and the Eurozone. The ECB is beginning to buy corporate bonds, including euro-denominated corporate bonds issued by US companies. This is pushing larger amounts of corporate euro bonds into the negative-yield absurdity. And it has opened all kinds of credit doors in the US.

But beneath the market euphoria, reality continues to plod forward.

Standard & Poor’s reported that among the companies it rates there were 12 defaults in May, which pushed its speculative-grade corporate default rate up to 4.1%, the highest since December 2010 when it was recovering from the Financial Crisis.

In January, so just five months ago, the default rate was still 2.8%. That’s how fast credit is deteriorating.

Even during the early phase of the Financial Crisis, in September 2008, when Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, and when all heck was breaking lose, the default rate was “only” 2.96%, before skyrocketing and eventually peaking at 12% in November 2009.

These are the largest US corporations, rated by Standard & Poor’s. But about 99% of the 19 million or so businesses in the US are small, generating less than $10 million a year in revenues, according to Dun & Bradstreet. None of them are rated by Standard & Poor’s, and none of them figure into its default rate. Another 0.96% or 182,578 businesses are medium-size with sales between $10 million and $1 billion. Only a smallish portion of them are rated by Standard & Poor’s, and only those figure into its default rate. The rest, the vast majority, are flying under Standard & Poor’s radar.

And how are they doing?

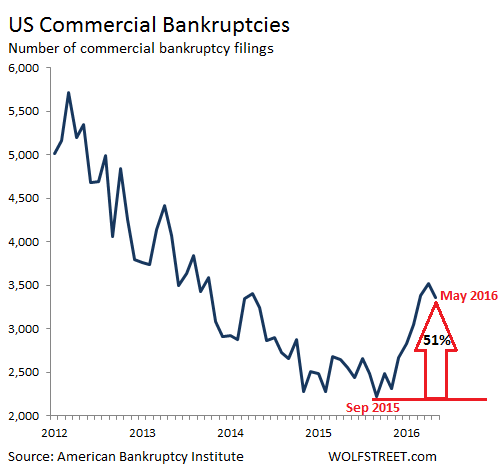

Here’s a clue: Total US commercial bankruptcy filings in May soared 32% from a year ago, to 3,358, the American Bankruptcy Institute (in partnership with Epiq Systems) just reported. It was the seventh month in a row of year-over-year increases in commercial filings.

“Businesses, especially those within the energy and retail sectors, continue to turn to the financial fresh start of bankruptcy,” the report said dryly. Among the various filing categories:

Chapter 11 filings (when a company “restructures” its debt, often wiping out stockholders and unsecured creditors, but continues to operate in the hope of emerging from bankruptcy with a more manageable load of debt) jumped 22% from a year ago, to 611.

Chapter 7 filings (when a company gives up its ghost and “liquidates” by selling its remaining assets and distributing the proceeds to creditors) soared 32% from a year ago, to 1,938.

Bankruptcy filings, like so many things, are highly seasonal. Monthly numbers depend on the number of filing days in that month, tax considerations, and so on. These are raw, unvarnished numbers. They’re not adjusted for seasonality or whatever. They’re volatile from month to month. But they do show the trend!

This chart shows how commercial bankruptcy filings have jumped since September 2015. Note the down-tick in May from April of 157 filings, which is normal for that month. The seven-year average of these April-May down-ticks is 194. The low point in commercial bankruptcies was in September 2015, with 2,217 filings. In the eight months since, they’ve soared 51%:

The chart puts a date on when the last credit cycle, that had started after the Fed kicked off the bailouts and QE in 2009, ended: September 2015. Then suddenly, bankruptcies began to soar. Other data place that point-estimate into different months, but they all agree that it was sometime in 2015, when credit contagion spread from energy to other sectors.

Commercial bankruptcies will continue to zigzag higher. This is among the consequences of seven years of desperately easy money: too much debt has piled up, and now companies are having trouble dealing with it while they’re struggling in an economy that is a heck of a lot tougher than the rosy scenarios projected year after year by economists on Wall Street, in government, and at the Fed.

This about sums up the US economy in more than one way. Read… How the Fed Stopped the “Corporate Profit Recession” (and the Media Fell for it)