View the high resolution version of this infographic

View the high resolution version of this infographic

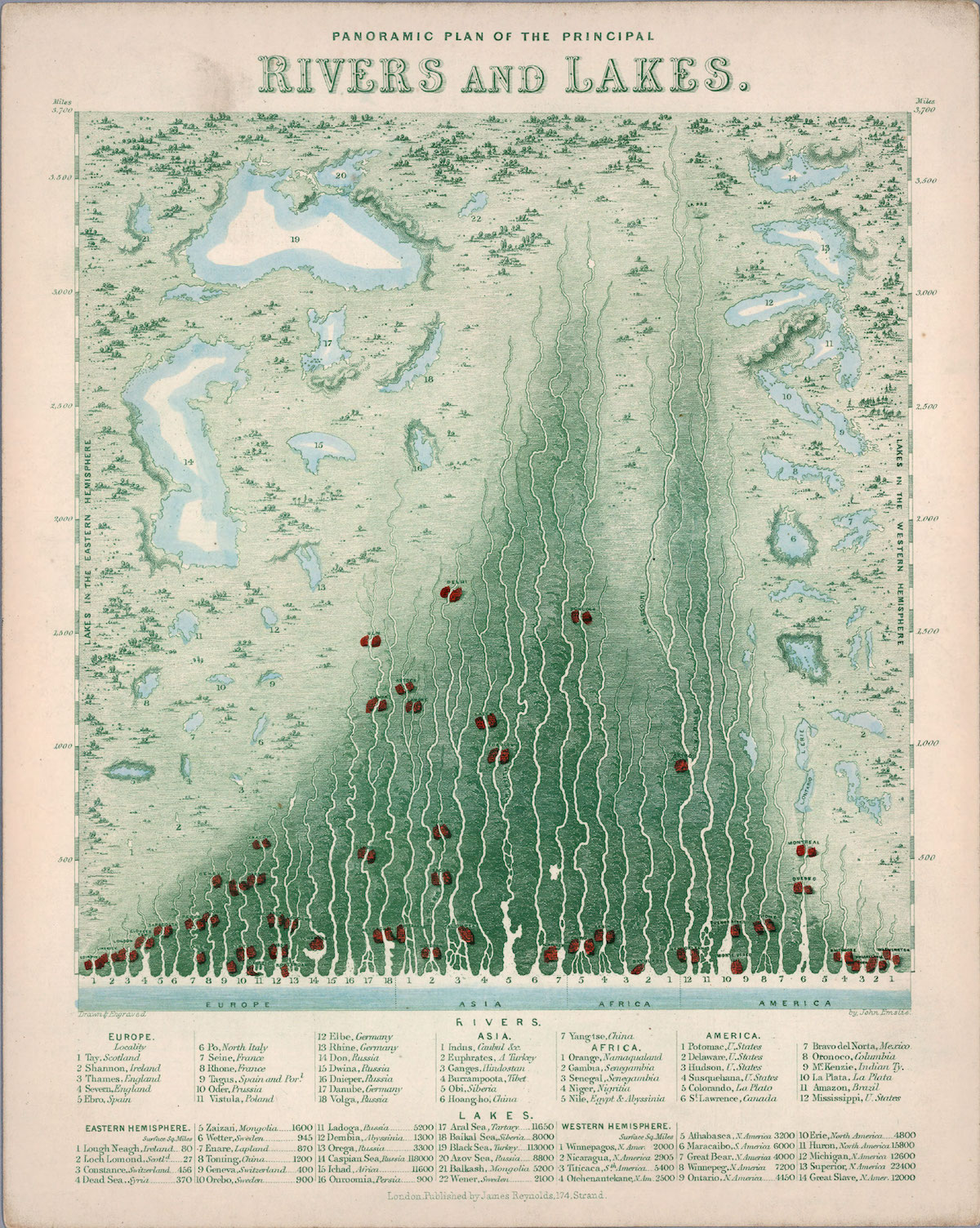

Vintage Viz: The World’s Rivers and Lakes, Organized Neatly

Rivers and lakes have borne witness to many of humanity’s greatest moments.

In the first century BCE, the Rubicon not only marked the border between the Roman provinces of Gaul and Italia, but also the threshold for civil war. From the shores of Lake Van in 1071, you could witness the Battle of Manzikert and the beginning of the end for the Byzantine Empire.

Rivers carry our trade, our dead, and even our prayers, so when London mapmaker James Reynolds partnered with engraver John Emslie to publish the Panoramic Plan of the Principal Rivers and Lakes in 1850, he could be sure of a warm reception.

The visualization, the latest in our Vintage Viz series, beautifully illustrates 42 principal rivers in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas, along with 36 lakes across the Eastern and Western hemispheres. Each river has been unraveled and straightened onto an imaginary landscape-–no meandering here—and arranged by size. Major cities are marked by a deep orangy-red.

Top 3 Longest Principal Rivers (in 1850)

According to this visualization, the Mighty Mississippi is among the world’s longest, coming in at 3,650 miles, followed by the Amazon, the Nile, and the Yangtze river in China. The bottom three are the Tay in Scotland (125 miles), the Shannon in Ireland (200 miles), and the Potomac in the U.S. (275 miles).

Surveying methods have come a long way since 1850, and we now have satellites, GPS, and lasers, so we can update these rankings. According to the CIA World Factbook, the Nile (6,650 km / 4,132 miles), the Amazon (6,436 km / 3,998 miles), and the Yangtze (6,300 km / 3,915 miles) are the world’s top three longest rivers.

The table below shows the rivers in the graphic above compared with today’s measurements, as well as the general location of rivers using 1850 location names (including modern day locations in brackets).

| River | Territory | Viz length (miles) | Modern length (miles) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mississippi | United States | 3,650 | 2,320 |

| Amazon | Brazil | 3,350 | 4,345 |

| Nile | Egypt and Abyssinia (Ethiopia) | 3,325 | 4,135 |

| Yangtse | China | 3,300 | 3,915 |

| Hoang-ho | China | 3,025 | 3,395 |

| Obi | Siberia | 2,800 | 2,268 |

| La Plata | La Plata (Argentina/Uruguay) | 2,450 | 3,030 |

| Volga | Russia | 2,200 | 2,193 |

| Burrampoota | Tibet | 2,200 | 1,800 |

| Ganges | Hindostan (India) | 1,975 | 1,569 |

| Euphrates | A(siatic) Turkey | 1,850 | 1,740 |

| Danube | Germany | 1,800 | 1,770 |

| Niger | Nigeria | 1,750 | 2,600 |

| Indus | Caubul etc (Afghanistan etc) | 1,700 | 1,988 |

| McKenzie | Indian Territory (Canada) | 1,600 | 1,080 |

| Senegal | Senegambia (Senegal) | 1,450 | 1,020 |

| Dnieper | Russia | 1,375 | 1,367 |

| Oronoco | Columbia | 1,325 | 1,700 |

| Gambia | Senegambia (The Gambia) | 1,300 | 740 |

| Bravo del Norta (Rio Grande) | Mexico | 1,150 | 1,900 |

| St. Lawrence | Canada | 1,125 | 1,900 |

| Orange | Namaqualand (Namibia/South Africa) | 1,100 | 1,367 |

| Dwina | Russia | 1,000 | 1,020 |

| Don | Russia | 975 | 1,198 |

| Rhine | Germany | 850 | 766 |

| Elbe | Germany | 750 | 724 |

| Vistula | Poland | 650 | 651 |

| Oder | Prussia (Germany) | 625 | 529 |

| Colorando | La Plato (United States) | 600 | 1,450 |

| Tague | Spain and Portugal | 575 | 626 |

| Susquehana | United States | 575 | 464 |

| Rhone | France | 550 | 505 |

| Seine | France | 475 | 485 |

| Po | North Italy | 450 | 405 |

| Hudson | United States | 425 | 315 |

| Ebro | Spain | 400 | 565 |

| Severn | England | 350 | 220 |

| Delaware | United States | 325 | 301 |

| Potomac | United States | 275 | 405 |

| Thames | England | 275 | 215 |

| Shannon | Ireland | 200 | 224 |

| Tay | Scotland | 125 | 117 |

These figures are a unique look into a time period where humanity’s efforts to quantify the world were still very much a work in progress.

Editor’s note: Some of the rivers and lakes are spelled slightly differently in 1850 than they are today. For example, the map notes today’s Mackenzie River (Canada) as the McKenzie River, and the Yangtze River (China) as the Yangtse.

O Say, Can You Sea?

The largest ‘lake’ in this visualization is the Caspian Sea (118,000 sq. miles), followed by the Black Sea (113,000 sq. miles), and the greatest of the Great Lakes, Lake Superior (22,400 sq. miles). While the Caspian Sea is considered a saltwater lake and could reasonably have a place here, the Black Sea—possibly bearing that name because of the color black’s association with “north”—is not a lake by any stretch of the imagination.

And while many of the surface areas reported could also be updated with modern estimates, the story behind Lake Chad (called Ichad in the visualization), the Aral Sea, and the Dead Sea are altogether different. Human development, unsustainable water use, and climate change have led to dramatic drops in water levels.

In another example, the Dead Sea had a surface area of 405 sq. miles (1,050 km2) in 1930, but has since dropped to 234 sq. miles (1,411.5 km2) in 2016.

| Lake | Territory | Viz surface area (sq. miles) | Modern surface area (sq. miles) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspian Sea | Russia | 118,000 | 143,000 |

| Black Sea | Turkey | 113,000 | 168,500 |

| Superior | North America | 22,400 | 31,700 |

| Huron | North America | 15,800 | 23,007 |

| Michigan | North America | 12,600 | 22,404 |

| Great Slave | North America | 12,000 | 10,500 |

| Aral Sea | Tartary (Central Eurasia) | 11,650 | 6,900 |

| Ichad | Africa | 11,600 | 590 |

| Azov | Russia | 8,800 | 14,500 |

| Baikal Sea | Siberia | 8,000 | 12,248 |

| Winnepeg | North America | 7,200 | 9,416 |

| Maracaibo | South America | 6,000 | 5,130 |

| Titicaca | South America | 5,400 | 3,030 |

| Ladoga | Russia | 5,200 | 6,700 |

| Balkash | Mongolia | 5,200 | 7,000 |

| Erie | North America | 4,800 | 9,910 |

| Ontario | North America | 4,450 | 7,340 |

| Great Bear | North America | 4,000 | 12,028 |

| Orega | Russia | 3,300 | 3,700 |

| Athabasca | North America | 3,200 | 3,030 |

| Nicaragua | North America | 2,905 | 3,149 |

| Otehenantekane | North America | 2,500 | 2,500 |

| Wener | Sweden | 2,100 | 2,181 |

| Winnepagos | North America | 2,000 | 2,070 |

| Zaizan | Mongolia | 1,600 | 700 |

| Dembia | Abyssinia (Ethiopia) | 1,300 | 1,418 |

| Tonting | China | 1,200 | 1,090 |

| Wetter | Sweden | 945 | 738 |

| Orebo | Sweden | 900 | 186 |

| Ouroomia | Persia | 900 | 1,126 |

| Enare | Lapland (Finland) | 870 | 1,040 |

| Constance | Scotland | 456 | 209 |

| Geneva | Swtizerland | 400 | 224 |

| Dead Sea | Syria | 370 | 605 |

| Lough Neagh | Ireland | 80 | 153 |

| Loch Lomond | Scotland | 27 | 27 |

You Can’t Step in the Same River Twice

Over time, natural and anthropogenic forces cause rivers to change their course, and lakes to shift their banks. If Reynolds and Emslie were alive today to update this visualization, it would likely look quite different, as would one made 100 years from now. But so goes the river of time.

The post Vintage Viz: The World’s Rivers and Lakes, Organized Neatly appeared first on Visual Capitalist.