Can I share this graphic?Yes. Visualizations are free to share and post in their original form across the web—even for publishers. Please link back to this page and attribute Visual Capitalist.

When do I need a license?Licenses are required for some commercial uses, translations, or layout modifications. You can even whitelabel our visualizations. Explore your options.

Interested in this piece?Click here to license this visualization.

▼ Use This Visualizationa.bg-showmore-plg-link:hover,a.bg-showmore-plg-link:active,a.bg-showmore-plg-link:focus{color:#0071bb;}

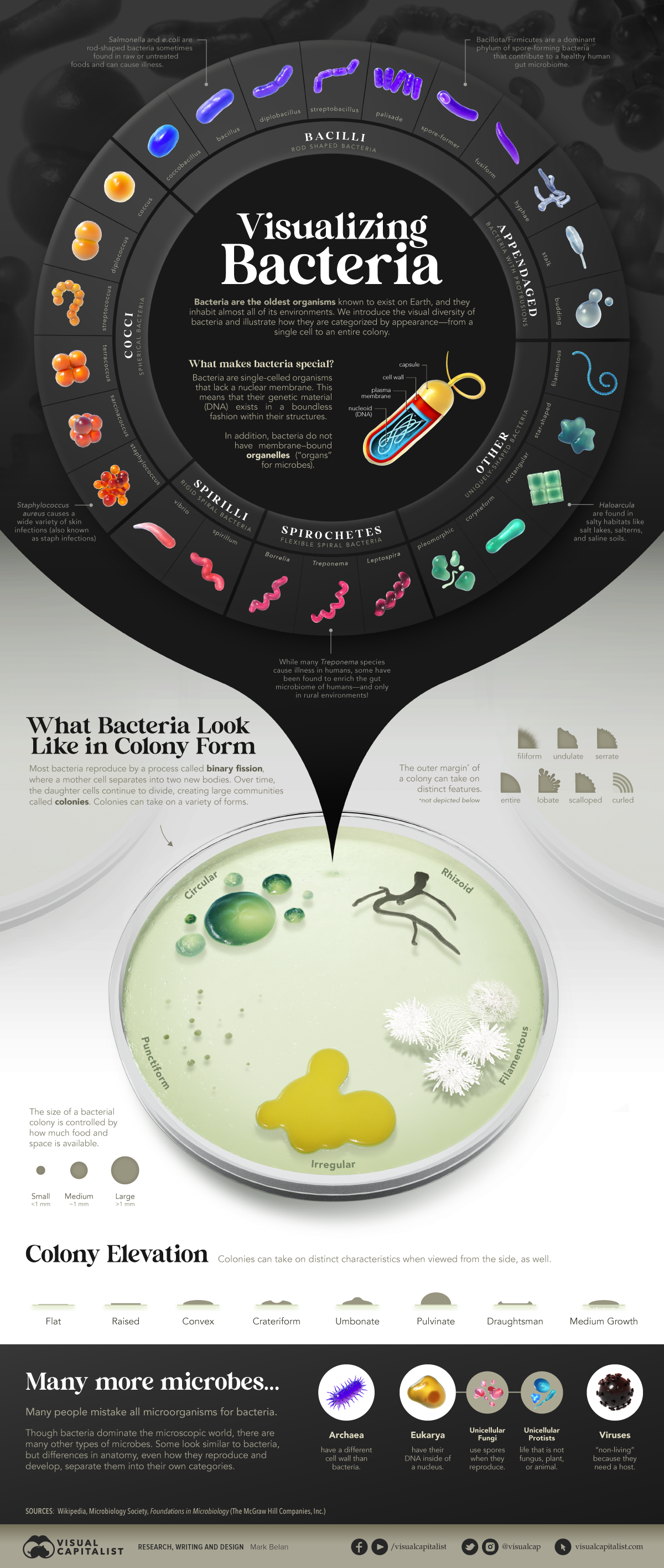

Invisible Diversity: The Many Shapes of Bacteria

Bacteria are amazing.

They were the first form of life to appear on Earth almost 3.8 billion years ago.

They make up the second most abundant lifeform, only outweighed by plants.

And most interesting of all: they exist in practically every environment on our planet, including areas where no other lifeforms can survive. As a result, bacteria exhibit a wide variety of appearances, behaviors, and applications similar to the lifeforms we see in our everyday lives.

The incredible diversity of bacteria goes underappreciated simply because they are invisible to the naked eye. Here, we illustrate how researchers classify these creatures on the basis of appearance, giving you a glimpse into this microscopic world.

A Life of Culture

Though bacteria may look similar to other microorganisms like fungi or plankton, they are entirely unique on a microscopic and genetic level.

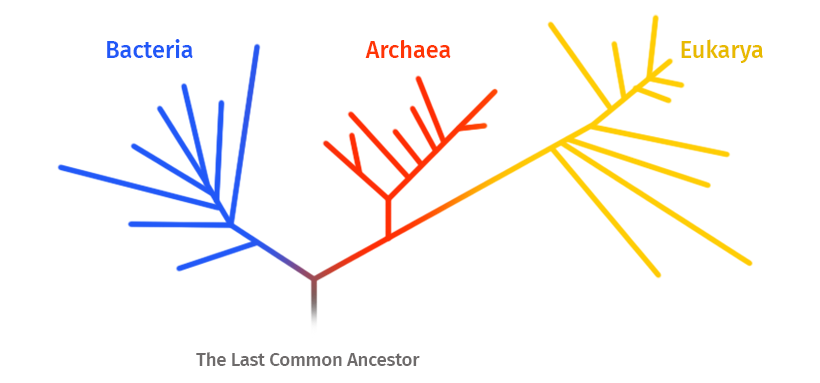

Bacteria make up one of the three main domains of life. All life shares its earliest ancestor with this group of microbes, alongside two other domains: the Archaea and the Eukarya.

Archaea are very similar to bacteria, but have different contents making up their cell walls.

Eukarya largely consists of complex, multicellular life, like fungi, plants, and animals. Bacteria are similar to its single-celled members because all bacteria are also unicellular. However, while all Eukarya have nuclear membranes that store genetic material, bacteria do not.

Bacteria have their genetic material free-floating within their cellular bodies. This impacts how their genes are encoded, how proteins are synthesized, and how they reproduce. For example, bacteria do not reproduce sexually. Instead, they reproduce on their own.

Bacteria undergo a process called binary fission, where any one cell divides into two identical cells, and so on. Fission occurs quickly. In minutes, populations can double rapidly, eventually forming a community of genetically identical microbes called a colony.

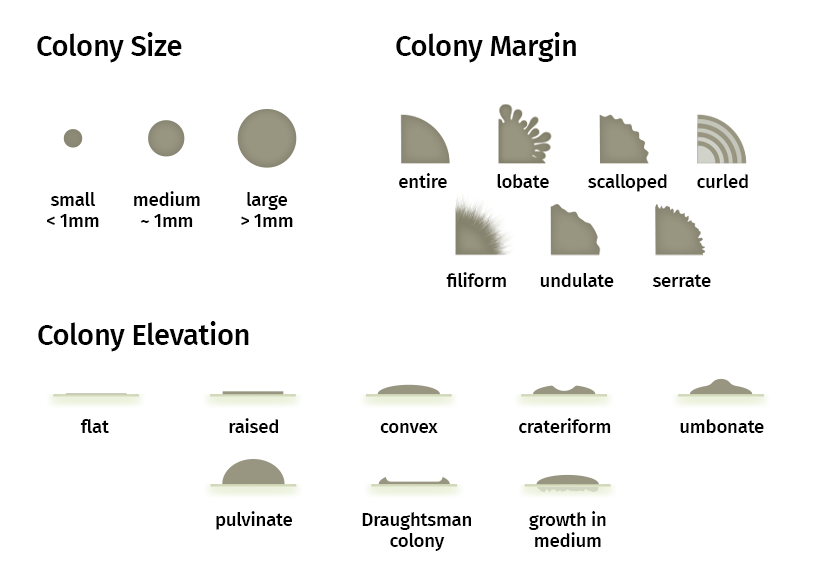

Colonies can be visible to the human eye and can take on a variety of different shapes, textures, sizes, colors, and behaviors. You might be familiar with some of these:

Superstars of a Tiny World

The following are some interesting bacterial species, some of which you may be familiar with:

Epulopiscium spp

This species is unusually large, ranging from 200-700 micrometers in length. They are also incredible picky, living only within the guts of sturgeon, a type of large fish.

Deinococcus radiodurans

D. radiodurans is a coccus-shaped species that can withstand 1,500 times the dose of radiation that a human can.

Escherichia coli

Despite being known famously for poisoning food and agriculture spaces from time to time, not all E.coli species are dangerous.

Desulforudis audaxviator

Down in the depths of a South African gold mine, this species thrives without oxygen, sunlight, or friends—it is the only living species in its ecosystem. It survives eating minerals in the surrounding rock.

Helicobacter pylori

Known for causing stomach ulcers, this spiral-shaped species has also been associated with many cancers that impact the lymphoid tissue.

Planococcus halocryophillus

Most living things cease to survive in cold temperatures, but P. halocryophillus thrives in permafrost in the High Arctic where temperatures can drop below -25°C/-12°F.

‘Bact’ to the Future

Despite their microscopic size, the contributions bacteria make to our daily lives are enormous. Researchers everyday are using them to study new environments, create new drug therapies, and even build new materials.

Scientists can profile the diversity of species living in a habitat by extracting DNA from an environmental sample. Known as metagenomics, this field of genetics commonly studies bacterial populations.

In oxygen-free habitats, bacteria continuously find alternative sources of energy. Some have even evolved to eat plastic or metal that have been discarded in the ocean.

The healthcare industry uses bacteria to help create antibiotics, vaccines, and other metabolic products. They also play a major role in a new line of self-building materials, which include “self-healing” concrete and “living bricks”.

Those are just a few of the many examples in which bacteria impact our daily lives. Although they are invisible, without them, our world would undoubtedly look like a much different place.

The post Visualized: The Many Shapes of Bacteria appeared first on Visual Capitalist.