Via John Hussman's Weekly Market Comment,

Since October, the economic evidence has shifted from supporting a growing risk of recession, to a guarded expectation of recession, to the present conclusion that a U.S. recession is not only a risk but an imminent likelihood, awaiting confirmation that typically only emerges after a recession is actually in progress. The reason the consensus of economists has never anticipated a recession is that so few distinguish between leading and lagging data, so they incorrectly interpret the information available at the start of a recession as “mixed” when, placed in proper sequence, the evidence forms a single, coherent freight train.

While I’m among the only observers that anticipated oncoming recessions and market collapses in 2000 and 2007 (shifting to a constructive outlook in-between), I also admittedly anticipated a recession in 2011-2012 that did not emerge. Understand my error, so you don’t incorrectly dismiss the current evidence. Though not all of the components of our Recession Warning Composite were active in 2011-2012, I relied on an alternate criterion based on employment deterioration, which was later revised away, and I relied too little on confirmation from market action, which is the hinge between bubbles and crashes, between benign and recessionary deterioration in leading economic data, and between Fed easing that supports speculation and Fed easing that merely accompanies a collapse.

Much of the disruption in the financial markets last week can be traced to data that continue to amplify the likelihood of recession. Remember the sequence.

The earliest indications of an oncoming economic shift are observable in the financial markets, particularly in changes in the uniformity or divergence of broad market internals, and widening or narrowing of credit spreads between debt securities of varying creditworthiness. The next indication comes from measures of what I’ve called “order surplus”: new orders, plus backlogs, minus inventories. When orders and backlogs are falling while inventories are rising, a slowdown in production typically follows. If an economic downturn is broad, “coincident” measures of supply and demand, such as industrial production and real retail sales, then slow at about the same time. Real income slows shortly thereafter. The last to move are employment indicators - starting with initial claims for unemployment, next payroll job growth, and finally, the duration of unemployment.

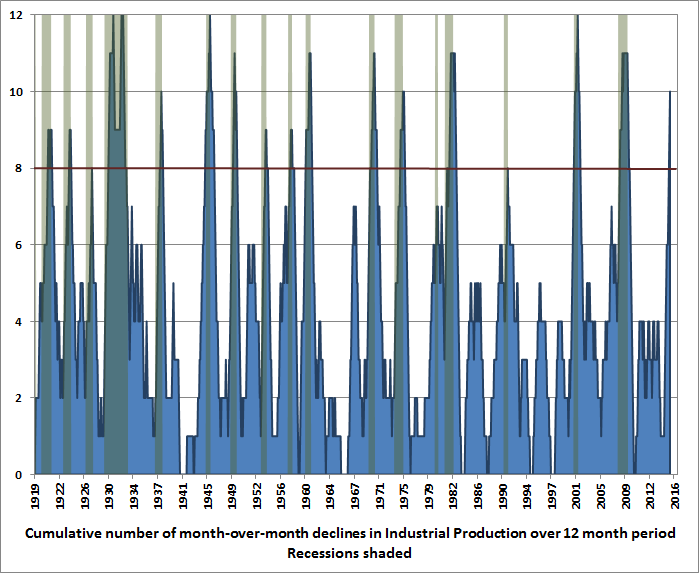

Last week, following a long period of poor internals and weakening order surplus, we observed fresh declines in industrial production and retail sales. Industrial production has now also declined on a year-over-year basis. The weakness we presently observe is strongly associated with recession. The chart below (h/t Jeff Wilson) plots the cumulative number of month-over-month declines in Industrial Production during the preceding 12-month period, in data since 1919. Recessions are shaded. The current total of 10 (of a possible 12) month-over-month declines in Industrial Production has never been observed except in the context of a U.S. recession. Historically, as Dick Van Patten would say, eight is enough.

A broad range of other leading measures, joined by deterioration in market action, point to the same conclusion that recession is now the dominant likelihood. Among confirming indicators that generally emerge fairly early once a recession has taken hold, we would be particularly attentive to the following: a sudden drop in consumer confidence about 20 points below its 12-month average (which would currently equate to a drop to the 75 level on the Conference Board measure), a decline in aggregate hours worked below its level 3-months prior, a year-over-year increase of about 20% in new claims for unemployment (which would currently equate to a level of about 340,000 weekly new claims), and slowing growth in real personal income.

Valuations, market internals, and crash risk

It’s largely irrelevant whether the Federal Reserve made a “policy mistake” by raising interest rates in December. As I’ve noted before, that would vastly understate the actual damage contributed by the Fed. The real policy mistake was to provoke years of yield-seeking speculation through Ben Bernanke’s deranged policy of quantitative easing. Just as the global financial collapse was the result of years of unbridled yield-seeking speculation in mortgage securities, the growing economic disruptions in the developing world are the result of years of unbridled yield-seeking capital flows that resulted from that policy, and the copycat behavior of other global central banks. The record ratio of corporate debt to corporate gross value added (GVA), and the elevation of equity market capitalizations to the highest ratio of GVA in history, outside of the 2000 bubble peak, have the same origins.

Understand that just as mortgage securities were the primary objects of yield-seeking speculation during the housing bubble, equity securities have been the primary objects during the QE-bubble. This is not merely because of direct speculation and record levels of margin debt among investors. As covenant-lite debt issuance soared in recent years, the primary use of the proceeds was not the accumulation of productive capital goods and equipment, but rather financial speculation in the form of acquisitions, leveraged buyouts, and corporate stock repurchases at historically rich valuations. Once valuations become obscenely elevated, a wicked downside is unavoidably baked in the cake. That downside will emerge primarily during periods such as the present, where deterioration in market internals suggests risk-aversion among investors, in contrast to the internal uniformity that prevailed until mid-2014, which reflected a broad willingness among investors to speculate and embrace greater exposure to risk assets.

To see how both corporate debt and equity capitalizations have soared to record levels relative to corporate GVA, and to understand why these imply dismal investment returns over the coming 10-12 years, see The Next Big Short: The Third Crest of a Rolling Tsunami. That commentary also includes a box detailing my own errors in the recent half cycle and the adaptations we introduced as a result, which require explicit deterioration in market internals (as we presently observe) before taking a hard-negative outlook. I openly discuss my own stumbles so that adherents and critics alike might benefit from the right lessons, before it becomes too late to do so.

We’ll certainly welcome outcomes that better reflect our experience in other complete market cycles, but we won’t do touchdown dances if the market collapses. The likely distress as the current market cycle is completed is something I wish on nobody. The unfortunate reality is that someone will have to hold stocks over the completion of this cycle, and it would best be those who have either carefully evaluated and dismissed our concerns, or those who have appropriate risk tolerances and investment horizons to weather the likely 40-55% loss in the S&P 500 that would comprise a rather run-of-the-mill retreat from the 2015 valuation extremes.

Our concerns about both the economy and the financial markets would be less immediate if we were to observe uniformly favorable market internals across a broad range of individual stocks, industries, sectors, and security types (including debt securities of varying creditworthiness). Instead, we currently observe negative leadership, weak breadth, and dismal participation, with only 17% of individual stocks still above their own respective 200-day moving averages. Meanwhile, credit spreads spiked to fresh highs last week.

On a short-term basis, dismal market internals may be indicative of oversold conditions, but the prospect of a recovery on that basis is extremely unreliable in an environment where valuations remain extreme and market internals demonstrate few positive divergences. I continue to believe that a break of the prior support area around 1820-1850 on the S&P 500 could be the catalyst for self-reinforcing panic selling pressure among trend-following investors.

Unfortunately, on historically reliable measures of value, current prices are nowhere near the levels that would be expected to produce adequate long-term total returns (see Rarefied Air: Valuations and Subsequent Market Returns). So there is presently an enormous chasm between the point where self-reinforcing selling pressure by speculators is likely to emerge, and the much lower point where balancing buying pressure by value-conscious investors is likely to support the market. Because every seller necessarily requires a buyer, the enormous gap between the two represents substantial crash risk.

Remember that our own central lesson in recent years was to avoid inadvertently prioritizing overextended conditions (e.g. overvalued, overbought, overbullish) over-and-above the condition of market internals. Provided that market internals are uniformly favorable, even obscenely overvalued markets tend to be resistant to severe losses, and are instead inclined to become even more overvalued. Conversely, it would be a mistake here to prioritize short-term oversold conditions over-and-above the dismal behavior of market internals and credit spreads, particularly given that overvaluation remains extreme on reliable measures. In the current environment, oversold conditions are prone to becoming even more deeply oversold, not only because internals are weak, but because the economic evidence is quickly confirming an oncoming recession that remains almost universally denied by market participants.