Authored by Axel Merk via MerkInvestments.com,

With the stock market and Bitcoin reaching all-time highs, what can possibly go wrong? In offering my thoughts on 2018, I see my role in reminding investors to stress test their portfolios. Is your portfolio built of straw, sticks or brick?

First, let me allege many investors have portfolios built of straw and sticks rather than brick. How do I know this? Here’s a brief check:

- If a robust portfolio is a diversified one (the only free lunch on Wall Street), then please check whether you have rebalanced your portfolio of late. If not, odds are equities have taken on an oversized portion in your portfolio, thus making it more vulnerable than you might have intended in a downturn.

- Equities are part of the so-called risk assets in a portfolio. But what about the rest of the portfolio? Have you been chasing yield by extending duration of your fixed income portfolio? Have you accepted less creditworthy issuers? Have you been lured by the promise of higher yields by financing something in a private placement? I have news for you: without judging the merits of those investments, odds are high that the value of these investments are more correlated with risk assets than you might be aware. Read: just because the label says fixed income doesn’t mean you are diversified.

Without a doubt, equities have had an extra-ordinary run. There is the view that, without a recession, you cannot have a bear market. In our analysis, that’s true for the most part – but is “for the most part” good enough? The notable exception is the Crash of 1987 where a bear market was not accompanied by a recession. In today’s context, the buy-the-dip crowd will remind you that the ’87 crash was, well, a buying opportunity. As such, if you are an asset manager interested in keeping your job, you buy. It reminds me of the 1980s where buying IBM office equipment was the sure way to keep your job, as no one would question your choice. Here’s a chart that shows the S&P 500 with the percent drawdown from any peak, with recessions shaded:

Keep in mind that we may not know about whether we are in a recession until we are well into it; also note the above chart is based on monthly data, thus not showing the maximum drawdown intra-month. That said, few economic forecasters are predicting a recession in the near future. Below is the quarter over quarter, seasonally adjusted GDP in black, then in grey the so-called Atlanta Fed GDPNow indicator, an indicator trying to predict the current quarter’s GDP reading:

So why be concerned? In a recent discussion with market veteran David Kotok (Chairman & CIO of Cumberland Advisors) regarding the views of an analyst who is optimistic about the outlook, he paraphrased Ronald Reagan’s debate with Walter Mondale: “I am not going to exploit his youth and inexperience…”, adding, “we will see if he knows how to swim.”

What are the optimists missing? First, let me make clear that you do not have to be a pessimist to be concerned. Risk assets are called risk assets for a reason: if you aren’t concerned, that should be the very first sign why you should be concerned. The prudent investor manages risk. However, risk management has become more complex in an era where central banks have helped propel asset prices to new highs; in an era where very low, if any returns can be had in so called risk-free assets. For European investors, returns are negative for many investment grade fixed-income investments, not just government securities. Monetary policy is indeed designed to encourage more risk taking. All the more so, when “risk is off”, i.e. when risk assets re-price lower, investors may be losing more money than they signed up for. If history is any guide, this could amplify any downturn as investors re-calibrate their portfolios to match their risk tolerance in an era when risk levels may be elevated once again.

Below, I’m highlighting a few factors that investors may want to pay particular attention to; this is not intended as a crystal ball, but food for thought.

First, the most obvious: a glass that’s considered half full can also be considered half empty. Facts don’t have to change for an assessment of those facts to change. What was a brilliant project may suddenly be considered a bottomless pit. Some say the recent under-performance of tech stocks is due to the fact that these firms already pay relatively low taxes and, thus, benefit less from lower corporate taxes than others. Have a look at this chart of some of Wall Street’s darlings. Is it yet another buying opportunity or have we seen the top in the markets?

Broader market indices reached new highs as those former market leaders have turned. That said, other market breadth indicators we monitor appear to show little concern.

Let’s switch to something that may very well be changing: the tax system. I’ll leave it up to tax pros to dissect the details, but would like to focus your attention on what I believe is an under-reported theme: there are incentives in the proposed tax legislation to limit the deductibility of interest expense. The potential new limits on deducting mortgage interest, but more relevant for the markets may be limits on deductibility of interest expense for corporations. While there are exceptions, it appears there will be caps on how much in interest expense is deductible for corporations (section 3301 of the GOP House bill). This will make it less attractive to do debt financing, more attractive to pursue equity financing. Less debt may be good news for financial stability, but it means the supply of equity may go up, thus causing potential downward pressure on prices.

Year-end tax optimization may also take on a new dimension this year, as large college endowments might race to reset the cost basis of their investments, assuming their gains will be subject to taxation going forward. In this context, it is quite plausible that the Santa Claus rally came early this year (the Santa Claus rally is a colloquial term for a year-end rally).

With regard to monetary policy, we are told a Powell Fed will be very similar to a Yellen Fed. I disagree: from what I have learned about Mr. Powell, he appears extremely well versed when it comes to bank regulation, but is agnostic when it comes to monetary policy. I have had to search long and hard to find original content on his monetary policy views. That’s not necessarily bad, but suggests that he will rely on others - presumably the staff at the Federal Reserve or possibly someone else on the FOMC Board - when it comes to setting monetary policy. My view is that the Fed is on auto-pilot until, well, until something disengages said autopilot. I can see Mr. Powell manage a financial crisis; but I do not think anyone knows how he will react when there are unforeseen surprises in the economy or the markets. My best guess is he’ll convene committees and come up with what appears to be a reasonable decision. The relevance being that markets don’t wait for committees to be convened. So if volatility shoots up in the markets, not just for a few minutes, but for weeks, substantial damage may be caused to risk assets. A textbook approach to monetary policy suggests that the Fed, not the markets are in charge, hence, why rush? Except that in an era of compressed risk premia and elevated asset prices, maybe, just maybe, the markets are in charge. If early 2016 is any guide, the Yellen Fed back-peddled promptly. As a new Fed Chair comes in with good intentions, I do not think Mr. Powell wants to be bullied by the markets.

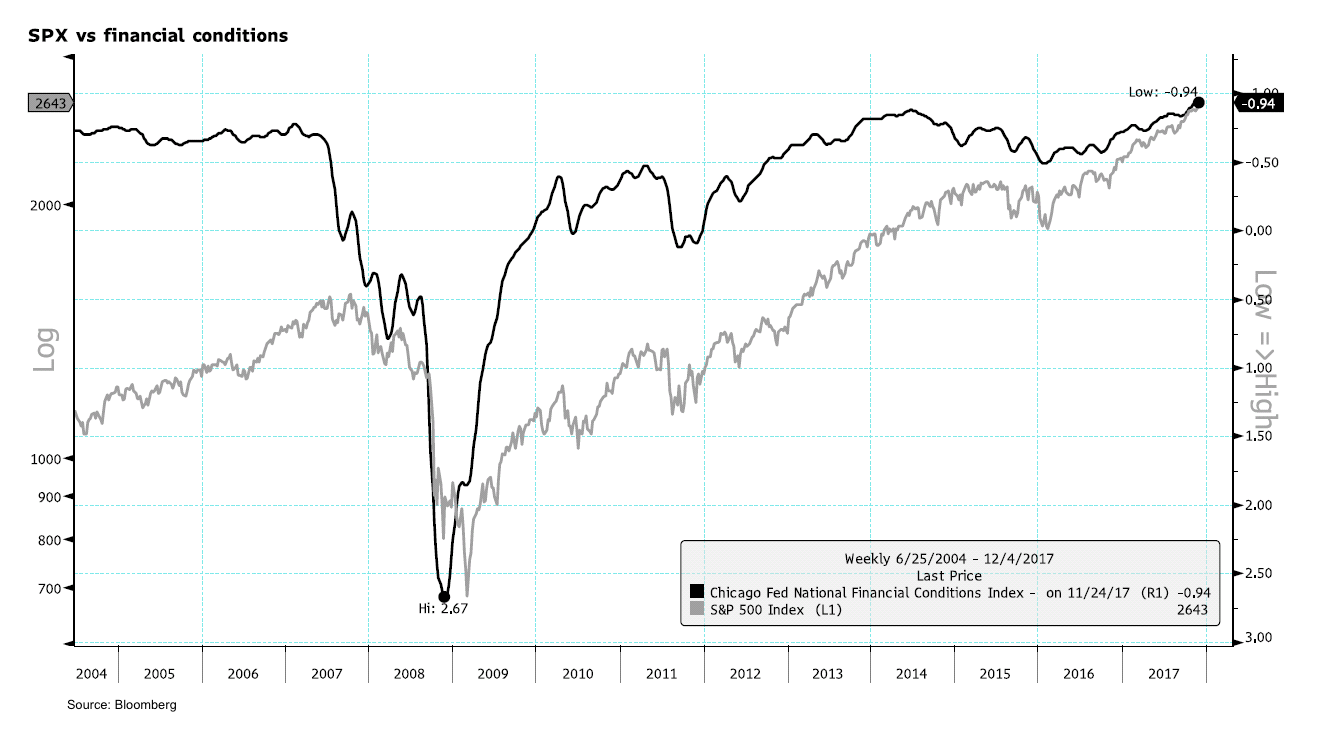

The Fed, of course, will never admit that they are slaves of the markets. They react to financial conditions. But what’s the difference? In normal times, there might be a big difference, but when central banks have made risk assets appear to carry only little risk, I argue that there isn’t much difference. Indeed, the reason Ms. Yellen tells us quantitative tightening (QT) is akin to watching paint dry on a wall is because she doesn’t want financial conditions to deteriorate as the Fed’s balance sheet is being reduced. In my humble opinion, that’s an oxymoron because both raising interest rates, as well as reducing the Fed’s balance sheet are inherently designed to tighten financial conditions. That’s the whole point! Except, of course, that financial conditions haven’t tightened:

The Fed can set interest rates, but doesn’t dictate how easy it is for borrowers to get credit. In a typical economic expansion, the Fed will start to raise rates to make it more expensive to borrow money (to tighten financial conditions!). But because the economy does well, banks might ease lending standards; or demand by borrowers may pick up for other reasons despite higher rates. As a result, the Fed continues to tighten until, well, until the economy at some point slows down. It’s this indirect dynamic that makes it so difficult for the Fed to engineer a soft-landing, i.e. to stop tightening just in time for excesses to be avoided. There’s a chance that the Fed will get this right. I just assign a very low probability to it.

So what does it mean for different asset classes:

It may well be that all the good news of the tax legislation is priced in, thus not causing equities to move and not causing Treasuries yields to move higher (part of the so-called Trump trade was higher Treasury yields reflecting higher long-term growth prospects).

- Equities: you be the judge. I don’t like where equities are, rather seek my returns elsewhere.

- Treasuries: many, including the Fed, suggest long-term rates ought to move higher, that the reducing of the Fed balance sheet will lead to higher long-term rates. I’m not convinced. My view is the Fed’s actions (together with fewer global central bank purchases) will lead risk premia to expand once again. That is, just as QE caused risk premia to come down, QT will push risk premia higher again, causing headwinds to risk assets. Read: there may well be a flight into Treasuries. Together with higher short-term rates, this a flattening of the yield curve. And that, in turn, is a sign of tighter financial conditions to come.

- Gold has been resilient despite higher rates. In my assessment, this has two reasons: one is that the Fed Funds rate has been very low, thus real yields have stayed low despite nominal rates inching up. More relevant may be that gold may be the easiest diversifier. I call it such because, in our analysis, the correlation to equities since 1970 is just about zero. To get non-correlated returns otherwise, you either need to move to cash (which many are reluctant to do) or embrace sophisticated long-short strategies (which many are also reluctant to do, albeit for different reasons).

- The dollar. Once again, there’s talk about the dollar rallying because growth prospects are better in the US. I would like to caution that the dollar rallied for many years on the prospect of Fed tapering. When it ultimately started, the dollar fell. Now we’ve started the process of taper talk at the ECB, but it is also a drawn-out affair. More so, the euro may have become a funding currency. That is, in risk-off environments, I’ve increasingly seen the euro rally. As such, the euro may be a diversifier for those concerned about risk assets.

As indicated, we don’t have a crystal ball, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have an opinion. We will discuss more in our December 12 outlook webinar (click to register). We will also give you food for thought for the global macro environment in the era of a Powell Fed. And if you are interested in a behind the scenes look at the sort of data we look at in our research meetings, we are working on a special report to share with those interested.