Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via The Daily Reckoning,

This is the reality: the American Dream is now reserved for the top 0.5%, with some shreds falling to the top 5% who are tasked with generating a credible illusion of prosperity for the bottom 95%.

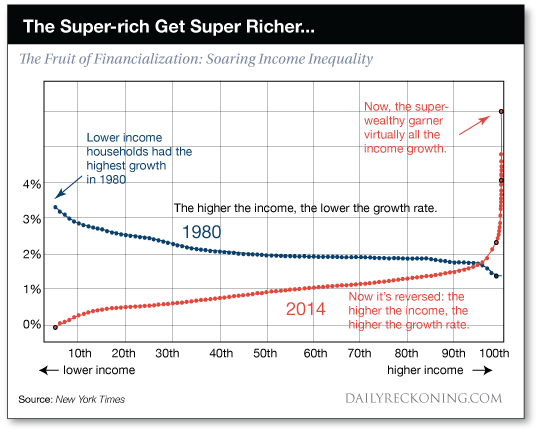

The question about who still has access to the American Dream is starkly answered by this disturbing chart:

If you talk to young people struggling to make ends meet and raise children, or read articles about retirees who can’t afford to retire, you can’t help but detect the fading scent of prosperity.

It has steadily been lost to stagnation, under-reported inflation and soaring inequality, a substitution of illusion for reality bolstered by the systemic corruption of authentic measures of prosperity and well-being.

In other words, the American-Dream idea that life should get easier and more prosperous as the natural course of progress is still embedded in our collective memory, even though the collective reality has changed.

For the bottom 95%, life is typically getting harder and less prosperous as the cost of living rises, wages are stagnant and the demands on workers increase.

Meanwhile, the asset bubbles inflated by central banks have enriched the top 10% of households, which own over 75% of all assets and take home over 50% of all household income.

The vast majority of household wealth is held by the top few households: the top .1% own roughly 25% of all US household wealth, the top 1% around 40%, and so on. So the households between 80% and and 95% own a very modest percentage of what the top 96%-99% own.

Median household income (using the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation, which grossly under-estimates real inflation) has gone nowhere since 2000. If income were adjusted by real inflation, it would show a 20% decline in purchasing power for all but the top 5%.

Clearly, our political-financial system and the policies of central banks have combined to concentrate wealth and income in the top of the wealth/income pyramid.

The average person knows the scent of the American Dream is fading, and many have lost hope of what was once taken for granted: home ownership, increasing income, and an easier life as household income and wealth slowly but surely increased with time.

But the collective memory of the American Dream remains; people feel they should be able to take a vacation, should be able to buy a starter home, should be free of constant worry about paying the bills, and so on.

With this collective memory still in place, people naturally start feeling a pervasive sense of betrayal: the system implicitly promised everyone who worked a lifetime security and increasing prosperity.

Official claims of prosperity are out of alignment with reality, and so expectations are out of alignment with reality. This creates a highly combustible and dangerous dynamic, as the emotions of betrayal and despair are volatile.

In other words, if 90% of the work force expects to be poor their entire lives, has no thought of ever owning a house, anticipates scraping by in their senior years, etc., then their expectations are aligned with the realities of a hierarchical power-law economy and social structure.

Low expectations are difficult to dash.

A sense of injustice and betrayal arise, along with a sense that something has gone profoundly wrong with the society and the economy.

This dynamic has yet to fully play out, but it will. Whatever you think of Trump, his election isn’t the problem; it’s merely a symptom of much deeper forces that will sweep our corrupt and rotten-to-the-core status quo into the dustbin of history.

But what can be done if you want to build a financial future?

Almost every asset class is in a bubble right now. So the question of where to invest one’s capital has become particularly vexing. Buying assets at nosebleed valuations in the hopes of earning another 5% aren’t very compelling to anyone pursuing common-sense risk management.

As it happens, I wrote a whole book on this vexing question, An Unconventional Guide to Investing in Troubled Times.

I can’t summarize all the ideas presented in the book in one brief article. But some basic principles will serve us well when bubbles abound.

1. Risk cannot be disappeared, it can only be masked or transferred to others. When anyone claims an investment is low-risk, they’re actually claiming either A) the risk has been obscured by fancy footwork or false claims, or B) the risk has been transferred to some mark, chump or bagholder — nowadays, that usually means the taxpayer, as profits are private and losses are socialized.

2. Value flows to what’s scarce. As economist Michael Spence and his colleagues have noted, conventional capital — the kind issued by central banks and private banks — is not scarce and therefore has little value. Ditto for conventional labor. This is why the returns on conventional capital and labor are so low.

Spence et al. suggest that what’s scarce in today’s global economy are ideas that create new business models, new productivity tools and new goods/services: labor, capital, and ideas in the power law economy.

This suggests an investment strategy of identifying what’s scarce, or what will soon be scarce, before everyone else.

3. Many things that are scarce and thus valuable cannot be bought on the global marketplace. The number one example of this is of course health, which is priceless because even having millions won’t buy your health back when it’s been lost.

Yes, you can get patched up with stents or costly meds or maybe score a black-market organ harvested from some unfortunate prisoner somewhere. But all this sort of thing merely keeps you alive; it doesn’t actually restore health.

So any investment in health will pay extremely high dividends. It doesn’t take a ton of cash to invest in one’s health; most of the investment is behavioral.

Other examples of what can’t be bought in the same way stocks, bonds and housing can be purchased: meaningful work, communities with a collective memory of how to get things done in the real world, a functioning community economy, etc.

Investing in work you find fulfilling and meaningful pays dividends that can’t be bought on the marketplace. Once again, investing in one’s skills and social/intellectual capital doesn’t require much cash. Thanks to YouTube University and many other free or low-cost sources, anyone can start acquiring the eight essential skills I lay out in my book Get a Job, Build a Real Career and Defy a Bewildering Economy.

The basic idea is to learn how to build your own career and job.

4. Comparing the relative value of various assets helps identify what’s relatively overvalued and undervalued. The key word here is relative: to say something is absolutely undervalued is trickier than concluding something is undervalued compared to other asset classes.

For example, compare housing in the U.S. and global commodities. Based on the national Case-Shiller Index, house prices have reached new bubblicious levels. Thanks, Federal Reserve!

It’s not much of a stretch to reckon that, hmm, valuations are looking a bit more likely to be overvalued here rather than undervalued. Meanwhile, commodities look decidedly unbubblicious at today’s levels.

But overall, this remains one of the most challenging environments we’ve known.