My friend Nathan Finn, Dean of the Theology school at Union University, has written a really interesting piece about the Benedict Option, from a Southern Baptist point of view. He calls is the Paleo-Baptist Option. Excerpts:

I argue the Paleo-Baptist Option has much to commend it for believers living in American Babylon, including many who don’t identify with the Baptist tradition. Baptists will best thrive in American Babylon by self-consciously framing ourselves as an ecclesiological renewal movement within the Great Tradition of catholic Christianity.

He goes on to talk about the historical roots of the distinctively Baptist form of Christianity, especially its creedalism. More:

With the exception of an emphasis on mission, among American Baptists these Paleo-Baptist priorities were either lost or redefined over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. Like other evangelicals, many Baptists embraced a radical form of biblicism that substituted what some have called solo scriptura for the Reformational principle of sola scriptura. Some went so far as to claim that creeds have no authority whatsoever—not even as a secondary authority under the supreme authority of Scripture.

Baptists increasingly interpreted historic Baptist principles such as congregational polity and local church autonomy through the lenses of Enlightenment individualism and Jeffersonian democracy. In terms of religious liberty, many Baptists advocated a version of strict church-state separation that emerged from the Enlightenment and has been identified with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

Finn calls on his fellow Baptists to rediscover and embrace their roots within their own tradition:

The time is ripe for Baptists in America to reclaim the Paleo-Baptist vision and commend it to all faithful Christians living in American Babylon. To borrow Dreher’s language, Paleo-Baptists are already committed to “construct[ing] local forms of community as loci of Christian resistance against what the empire represents.” We call them local churches, and in the Paleo-Baptist vision, churches are counter-cultural communities of disciples who covenant to walk together for the sake of worship, catechesis, witness, and service.

To those like Dreher who are drawn to neo-monastic movements, Paleo-Baptists would say that a covenantal understanding of church membership accomplishes the same goal, but applies it to all church members, which we believe closely follows the New Testament vision of the church. When membership is restricted to professing believers, churches become the most natural context for theological and moral formation and intentional discipleship.

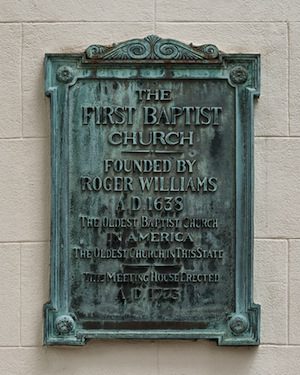

Nagel Photography / Shutterstock.com

Though pragmatic forms of revivalism and populist versions of patriotism have distracted many Baptists, the Paleo-Baptist vision is making a comeback. Groups such as 9 Marks Ministries advocate historic Baptist ecclesial priorities, but do so in a way that also appeals to many other low church Protestants such as Presbyterians, Bible Churches, Evangelical Free congregations, and even many non-denominational evangelicals. Public intellectuals such as Russell Moore and Bruce Ashford have urged American evangelicals to ratchet-down their propensity to identify the GOP with God’s Own Party and have called upon all believers to be an orthodox counter-culture for the common good. These Paleo-Baptist calls resonate with many Baptists and many other believers, especially among the millennial generation.

He goes on to say that Baptists have a lot to learn from Christians in the older, liturgical traditions, and ought to reframe themselves in a more small-c catholic way, as part of the “Great Tradition” of Christianity. And he says — correctly, in my view — that Baptists have a lot to teach the rest of us about evangelism, and the importance of evangelical zeal.

Read the whole thing. There’s more to it than I could convey here without overquoting.

First, let me say that if I haven’t talked much about evangelism in my Ben Op writing, it’s not because I think it’s unimportant. It’s because that I focus more on discipleship, which I find generally lacking in all American Christianity. But it is undeniable that Baptists and other Evangelicals have a lot to teach Catholics, Orthodox, and Mainline Protestants about evangelism. You’ll see when I publish the Ben Op book that the idea of the Ben Op being quietist is simply mistaken. It’s not an either/or. Brother Ignatius, one of the Norcia monks, says we must always be “advancing,” not retreating. But he also recognizes that in order to advance, we must train and build our spiritual strength in ways that are too often neglected by Christians today.

Yesterday I received an e-mail from a reader with knowledge of missionary work overseas. He told me about certain practices that missionaries undertake to withdraw from time to time for spiritual recharging, and to help each other by intense communal life with other Christians. They are there to spread the Gospel, certainly, but those who work in hostile countries and cultures, says this reader, “know that without deliberate and strategic withdrawal, Christians will quickly either burn out or acculturate.”

We Christians in post-Christian America are going to have to learn those skills from missionaries, I believe.

Let me thank Nathan heartily for this essay. This is exactly the kind of creative thinking and conversation that I hope the Benedict Option project will start among small-o orthodox Christians of all churches and traditions. It is futile to make its success depend on everyone converting to this or that church or tradition, including my own. But if we can get folks to explore deeply in their own particular tradition, and deep into Christian history, then they may find the resources to make themselves and their communities more resilient in this increasingly hostile world.

If I could have everybody read one book to this end, it would be church historian Robert Louis Wilken’s The Spirit of Early Christian Thought. It’s written for non-academics, and it makes the thinking and way of life of the early Church, and the era of the Fathers, come vividly to life. Wilken is a beautiful writer. The early Christians, men and women who lived out the faith in a non-Christian (or barely Christian) culture, are our common ancestors in the faith, and they are a great place for us Christians of the 21st century to seek guidance, inspiration, and commonality.