Authored by Nick Cunningham via OilPrice.com,

The IMF estimated that Saudi Arabia will need oil prices to trade at about $70 per barrel in 2018 for its budget to breakeven, a dramatic improvement from the $96.60 per barrel it needed just last year. Saudi’s improvement is the most dramatic out of all the Middle Eastern oil producers, and it also suggests the combination of austerity, cuts to wasteful subsidies, new taxes and economic reforms are starting to bear fruit.

The improvement is all the more important because Saudi Arabia and its fellow OPEC members are restraining output as a way to boost oil prices. Selling fewer barrels means less revenue, although that is offset by the coordinated production cuts through the OPEC deal, which has helped raise prices.

Nevertheless, there is something glaring about Saudi Arabia’s breakeven price: It is still far higher than the current oil price, which means Riyadh is still feeling the economic and fiscal pressure from low crude prices. “The reality of lower oil prices has made it more urgent for oil exporters to move away from a focus on redistributing oil receipts through public sector spending and energy subsidies,” the IMF said in its report. Saudi Arabia and other Middle East oil producers “have outlined ambitious diversification strategies, but medium-term growth prospects remain below historical averages amid ongoing fiscal consolidation,” the IMF added. In other words, austerity might help narrow the budget deficit to some degree, but it can also be self-defeating if it slows growth.

Saudi Arabia may have posted the largest drop in its breakeven price, but several of its peers have even lower budgetary thresholds. Iran, Iraq, Kuwait and Qatar all breakeven at $60 per barrel or less in 2018, meaning they will likely avoid a fiscal deficit.

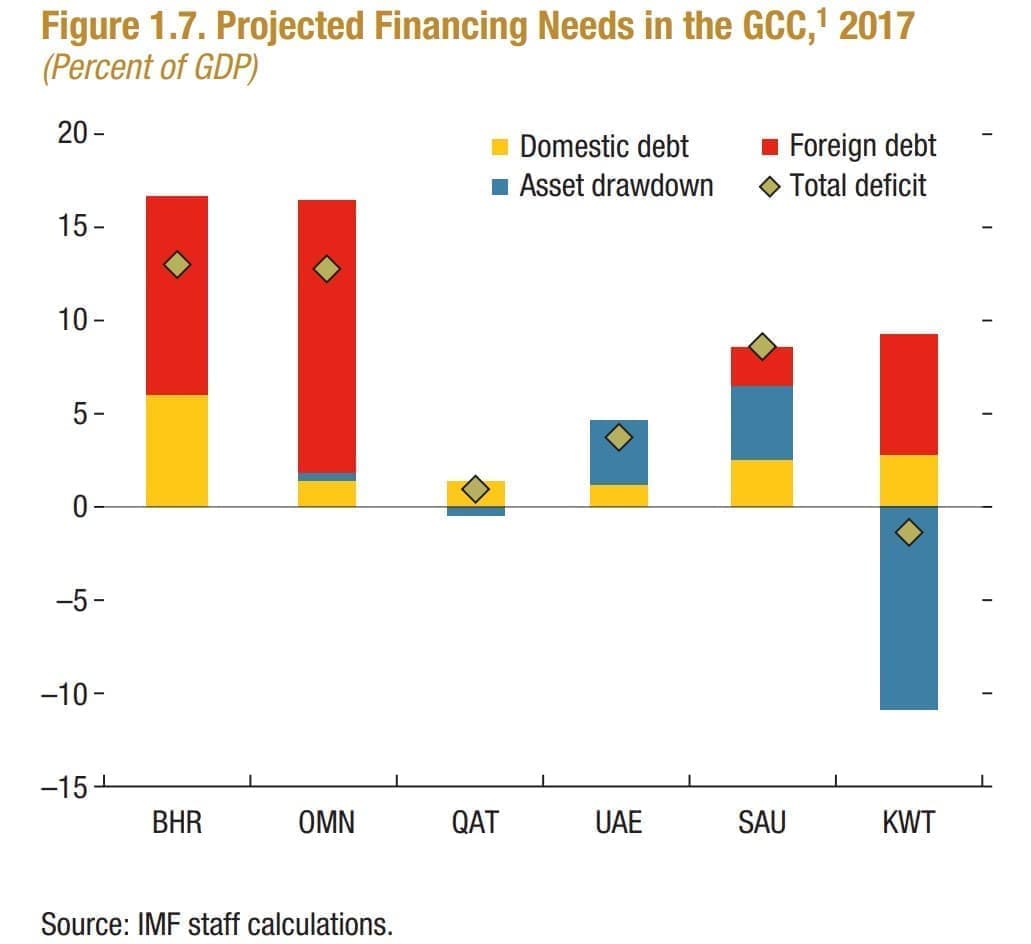

Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, will take much longer to balance its budget, the IMF warned. It is expected to post a $53 billion deficit this year. That means it will likely have to continue to turn to international and domestic debt markets to plug its budgetary gap, while also burning through cash reserves. Last year, Saudi Arabia issued $17.5 billion in international debt, the largest debt issuance ever sold in emerging markets. Earlier this year it sold $9 billion sukuk, or Islamic bonds.

In September, Riyadh sold another $12.5 billion in bonds, the largest global debt sale in 2017.

It also has burned through over $200 billion in cash reserves since it hit a peak a few years ago.

(Click to enlarge)

The slated IPO of Saudi Aramco should be viewed in this context. It will provide the government with an injection of cash, which it hopes to use to further develop parts of the economy unrelated to oil. Saudi officials have hyped the IPO, boasting that it could lead to $100 billion in proceeds, assuming a $2 trillion valuation of Aramco. Independent analysts have argued that the actual figure will likely be far lower.

Saudi Arabia’s determination to boost the oil prices is also directly related to its fiscal problems. While there are tradeoffs to such an approach – voluntarily restraining output is an enormous sacrifice – there is no doubt that Saudi officials fear another oil price downturn. While it has taken a lot longer than they thought, the OPEC/non-OPEC production cuts have helped erase a large chunk of the global oil surplus, and oil prices are now at their highest level in nearly two and a half years. Now is not the time to take the foot off the gas. The deputy crown prince recently voiced his support for an extension of the OPEC deal at the upcoming meeting on November 30. With Russian support likely, an extension is all but a done deal.

That should help to continue tighten the market, which could ultimately lead to gradual increases in oil prices. There are rumors that Saudi Arabia might abandon its Aramco IPO, or keep it on its domestic exchange, but higher oil prices might ease concerns about the offering.

Still, the IMF – as well as a long line of oil analysts – don’t see oil prices returning to $70 per barrel anytime soon. That means that Riyadh will have to redouble its efforts to cut down on its deficit. But it will likely be years before the Saudi budget breaks even.