Authored by Wolf Richter via WolfStreet.com,

But savers are still getting shafted.

Outstanding “revolving credit” owed by consumers – such as bank-issued and private-label credit cards – jumped 6.1% year-over-year to $977 billion in the third quarter, according to the Fed’s Board of Governors. When the holiday shopping season is over, it will exceed $1 trillion. At the same time, the Fed has set out to make this type of debt a lot more expensive.

The Fed’s four hikes of its target range for the federal funds rate in this cycle cost consumers with credit card balances an additional $6 billion in interest in 2017, according to WalletHub. The Fed’s widely expected quarter-percentage-point hike on December 13 will cost consumers with credit card balances an additional $1.5 billion in 2018. This would bring the incremental costs of five rates hikes so far to $7.5 billion next year.

Short-term yields have shot up since the rate-hike cycle started. For example, the three-month US Treasury yield rose from near 0% in October 2015 to 1.33% today. Credit card rates move with short-term rates.

Mortgage rates move in near-parallel with the 10-year Treasury yield, which, at 2.39%, has declined from about 2.6% a year ago. Hence, 30-year fixed-rate mortgages are still quoted with rates below 4%, and for now, homebuyers have been spared the impact of the rate hikes.

Auto loans, in line with mid-range Treasury yields, have wavered a lot and moved up only a little. The average APR on a 48-month new-car loan rose only 40 basis points over the past two years to 4.4% in August 2017, according to WalletHub, citing the most recent data available. Note that the offers of “0% financing” are usually in lieu of rebates or other incentives and are therefore rarely free.

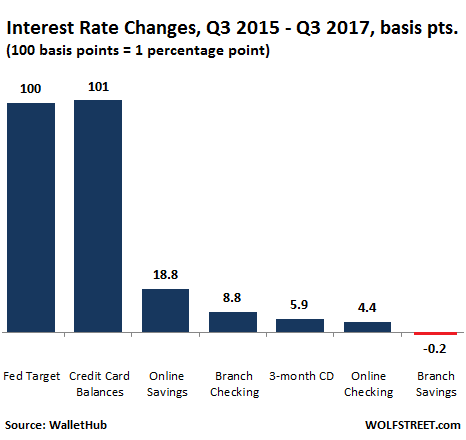

The chart below shows the increase in the Fed’s target for the federal funds rate, from 0-0.25% to 1-1.25% (not including a hike on December 13), so an increase of 100-basis points. Credit card rates have increased in lockstep by 101 basis points. But bank deposits rates have lagged woefully behind, on the logic that credit-card borrowers and savers, both, are going to get shafted:

So how do these rate hikes translate for households with credit card balances?

Revolving credit outstanding of $1 trillion, spread over 117.72 million households, would amount to $8,300 per household. But many households do not carry interest-bearing credit card debt; they pay their cards off in full every month. Finance charges are concentrated on households that use this form of debt to finance their spending and that cannot pay off their balances every month. Many of these households are already strung out and are among the least able to afford higher interest payments.

Consumer credit bureau TransUnion shed some light on this in its Q3 2017 Industry Insights Report, according to which 195.9 million consumers had a revolving credit balance at the end of Q3, with total account balances of $1.35 trillion. This equals $6,892 per person with revolving credit balances. If there are two people with balances in a household, this would amount to nearly $14,000 of this high-cost debt. If the average interest rate on this debt is 20%, credit-cart interest payments alone add $233 a month to their household expenditures.

What is next for these folks?

For now, the Fed has penciled in, and economists expect, three hikes next year. But recent developments – particularly the expected tax cuts and what the Fed calls “elevated asset prices” – suggest that the Fed might “surprise” the markets with its hawkishness in 2018.

The Fed is currently pegging the “neutral” rate – the rate at which the federal funds rate is neither stimulating nor slowing the economy – at somewhere near 2.5% to 2.75%, so about five or six more rates hikes from today’s target range.

Interest rates on credit cards would follow in lockstep. These rate hikes to “neutral” would extract another $8 billion or so a year, on top of the additional $7.5 billion from the prior rate hikes.

But that’s not all. Credit card balances continue to rise as our brave consumers are trying to prop up US consumer spending and thus the global economy by borrowing more and more. Thus, rising credit card balances combined with rising interest rates on those balances conspire to produce sharply higher interest costs.

Since consumers with high-interest credit-card balances already don’t have enough money to pay off their costly debt, these additional interest payments will further curtail their efforts at making principal payments and thus inflate their credit card balances further.

For many consumers whose credit is already challenged, this scheme eventually ends in default. Credit card delinquencies have started to tick up, from 2.16% in Q1 2016 to 2.53% in Q3. While still soothingly low overall, the damage is always concentrated in the subprime segment – and on lenders that specialize in subprime lending. And there, delinquency rates are jumping. Yet these are still the best of times, with the lowest unemployment rate since the year 2000.

This parallels the delinquencies in auto loans. The 90+ day delinquency rate for loans originated by auto finance companies has hit 9.7% in Q3 2017, the highest since Q1 of 2010, when it was on the way down from the Financial Crisis. Delinquencies first hit that rate on the way up in Q3 2008, during the Lehman moment. But now, there is no Financial Crisis. These are the boom times.

Read… Auto-Loan Subprime Blows Up Lehman-Moment-Like