Submitted by Axel Merk via Merk Investments,

"The Fed doesn't have a clue!" - I allege that not only because the Fed appears to admit as much (more on that in a bit), but also because my own analysis leads to no other conclusion. With Fed communication in what we believe is disarray, we expect the market to continue to cascade lower - think what happened in 2000. What are investors to do, and when will we reach bottom?

To understand what's unfolding we need to understand how the Fed is looking at the markets, and how the markets are looking at the Fed.

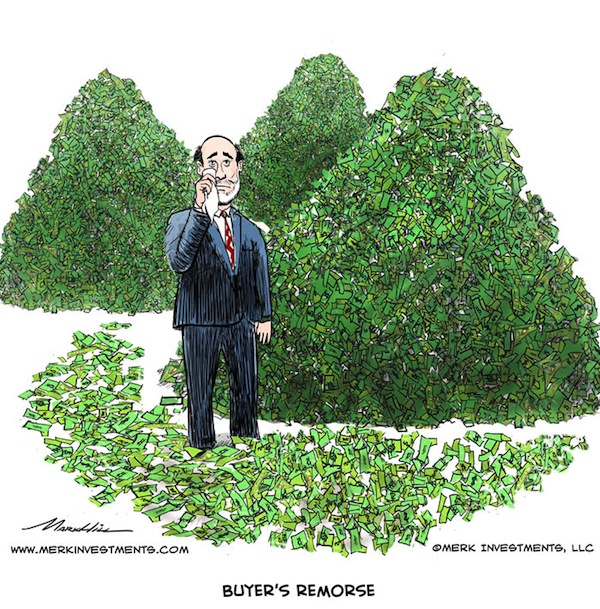

The Fed and the MarketsIn our analysis, policies at the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) are driven by what the Fed Chair deems most important. At the risk of oversimplification, and to zoom in on what I believe is relevant in the context of this discussion, former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan put a heavy emphasis on the 'wealth effect;' in many speeches, both during and after his tenure at the Fed, he indicated that rising asset prices would be beneficial to investment and economic growth. His successor Ben Bernanke went as far as mentioning in FOMC Minutes rising equity prices as a beneficial side effect of quantitative easing (QE). Bernanke's framework, though, was indirect: he considered himself a student of the Great Depression, arguing that monetary accommodation shouldn't be removed too early when faced with a credit bust, as doing so might unleash deflationary forces once again. QE, of course, 'printed money' to buy Treasuries and Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS), i.e. intentionally sought to increase their prices (I take the liberty to call QE the printing of money because, amongst others, Bernanke himself has referred to QE as such; no physical money is printed, but it's created 'out of thin air' through accounting entries at the Fed).

This prelude is necessary to understand Janet Yellen, a labor economist. I am not aware of labor economists focusing on equity prices. Neither am I aware that labor economists use forward inflation expectations as a gauge to predict labor markets. Sure enough, any FOMC member is likely to look at various indicators of inflation in the course of their job, but for a labor economist, it may merely be yet another data point. The reason I say this is because, during Bernanke's tenure, when inflation expectations dipped towards the 2% threshold, he would talk about the need for QE (the chart shows a measure of longer term inflation expectations):

[image]https://www.merkinvestments.com/images/2016/2016-02-09-5y5y.jpg[/image]

In contrast, Janet Yellen has been rather quiet about the chart, instead pointing to other surveys that show long term inflation expectations remain well anchored. Interestingly, Mr. Draghi at the European Central Bank (ECB) looks at a similar chart of the Eurozone inflation expectations and rings the alarm bell, suggesting policy action may be needed to get those inflation expectations higher once again.

A labor economist is, in my assessment, destined to look at stale data, as jobs data tend to be backward looking. With what I believe is a 'backward looking' framework, the Fed may well be clueless: in their latest FOMC statement, the Fed removed their view that risks are balanced in favor of saying that the balance to risks needs further assessment. That is, I allege the Fed no longer has a view of where we are in the economy; it looks like I am not the only one with that interpretation, even Vice Chair Stan Fischer has indicated they need to wait for more incoming data to assess the economy. It's one of the reasons the Fed may look ever more like a huge ocean tanker that's slow to move. The fact that the Fed may be slow to move and not be quite as activist is not a bad thing per se, but needs to be understood in the context of how the markets will behave.

The Markets and the FedLet's look at the flip side: the market. For years, asset prices were rising on the backdrop of low volatility. That low volatility was, in my assessment, induced by highly accommodative monetary policy. I like to refer to it as an era of 'compressed risk premia.' In that environment, I allege investors got over-exposed to risky assets; that's a rational reaction to a world that is perceived to be less risky. But, of course, I would argue the world is still a risky place; it's only that the risk has been suppressed. As such, whenever the Fed started to contemplate an exit, I would say the market threw a 'taper tantrum,' then, last August, the Fed suggested it really meant business, although it got cold feet yet again, at least for a few weeks. It was too late, though: I visualize it as the Fed opening the lid to the pressure cooker it had left on the hot plate for too long.

As a result, investors may be waking up to the notion that markets are risky after all and that they must sell risky assets (equities, junk bonds, amongst others) to rebalance their portfolios. As a result, investors may be increasingly interested in capital preservation, i.e. 'sell the rallies' rather than 'buy the dips.'

The Yellen Fed, looking at this, may shrug it off for two reasons: first, they may realize they made a mistake when they caved in to the markets, postponing the September rate hike. After all, if they blink because of a hiccup in the markets, they become slaves to the markets. That's a fair point, but in my opinion, the reason the Fed is a slave of the markets is because they've made themselves a slave of the markets with their emphasis on 'data dependency.' It's not that relying on data is a bad idea per se, but if the Fed is not clear on how it interprets what, with the only certainty that there's a heavy emphasis on backward looking employment data, one does not need to be surprised that the market is imposing its own views on the Fed rather than the other way around.

What does it mean for investors?For investors, I believe it means that market forces are taking the upper hand – for now. That may be a good thing if you are short 'risk assets' (notably equities): as the steam is released from the pressure cooker, asset prices may deflate once again. It's the sort of scenario Bernanke might be terrified about, as the 'progress' of QE may be undone. A Yellen Fed may rightfully say that it's not their job to keep equity prices high, and that she is more concerned about the labor market. That's all well and good, except that the recovery was, in our assessment, largely based on asset price inflation. As such, when asset prices plunge, it also provides a headwind to the real economy.

Mr. Draghi at the ECB and Mr. Kuroda at the Bank of Japan (BoJ) may well see that and try to counter what they may perceive as an alarming development. Yet, we feel it's the Fed that's the biggest elephant in the room (it's the issuer of the worlds reserve currency and given the amount of global dollar credit that's been raised since 2008, it may effectively be the emerging markets' central bank); in that context, the bazookas of the ECB and BoJ may appear as mere water pistols.

Yellen, if we are not mistaken, may only react in earnest once the effect is felt on the real economy. It also means that what we believe is a bear market will be able to play out in full. Keep in mind also that some of the necessary adjustments in the marketplace will take some time to play out: low interest rates may allow many otherwise unsustainable businesses to stick around until they need to refinance their debt. As such, the adjustment in the oil sector, for example, may take much longer; and it's not just on the corporate side, as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) may be extending loans to governments of oil producing countries, thus also contributing to elevated global oil production.

In practice, the selling may end when most investors have shifted towards a capital preservation mode. This won't be a straight line, as bear markets can have violent rallies. And not only will the BoJ and ECB not sit idle on the sidelines, but ripple effects may go through the markets as the Fed is gradually coming to grips with reality.

How to get out of this mess?Some have suggested that my assessment equates to an endorsement of more QE or negative rates. Absolutely not. To get out of this mess, I say the same thing I said in 2008: the best short-term policy is a good long-term policy. What's a good long-term policy when governments around the world have, as I believe, too much debt and low growth? Based on my analysis, the answer must be in monetary or fiscal policy to make debt sustainable as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The successful investor should be able to navigate how different countries address these challenges. In that context, it matters little what I think should happen, given my framework. It may matter more what will happen given the policymaker's framework.

But since you asked, I believe the answer is not in monetary policy. You cannot print your way to prosperity. That path risks destroying purchasing power and a destruction of the middle class. The result may be public resentment, the rise of populist politicians and reduced political stability, even war.

When it comes to fiscal policy, there are more choices than are commonly discussed. First, the extension of 'printing money' on the fiscal side would be a form of default. We've already heard some say that the Bank of Japan should simply wipe out the debt it has purchased in the markets. As a central bank, writing off such debt is a mere accounting entry, as central banks can live on with negative equity. Some debt will need to be restructured, and indeed, I believe much of the work in the Eurozone has been to get the financial system strong enough to stomach a sovereign default.

Fiscal policy can also be the pursuit of austerity. It works for Germany, but not for Greece. In Greece and many other countries, it causes popular backlash that can destabilize a country.

Then there is a pursuit of growth, typically associated with massive fiscal spending programs. Bond king Bill Gross has indicated we need to have fiscal expansion as monetary policy has reached its limits. So has the head of the world's largest hedge fund, Ray Dalio.

Unfortunately, the only 'fiscal stimulus' that I know that can break the deflationary cycle is war. That's what we got after the Great Depression, and I don't look forward to a repeat.

Instead, I believe there must be a better way. That better way, in my view, is an expansionary fiscal policy that is sustainable. Fiscally sustainable policies are long-term pro-growth strategies that don't themselves blow up the debt. On the cost cutting side, it includes entitlement reform to make deficits sustainable; such a policy is pro-growth because investors are more likely going to allocate money when they see fiscal policy is sustainable. On the revenue side, rather than plow huge amounts into fiscal expansion by the government, the cutting of red tape can go a long way towards unleashing growth. Over the past 15 years, I believe red tape has increased rather dramatically in many sectors, inhibiting growth.

But, alas, since it seems policy makers are unlikely to pursue what I believe is necessary, we need to think about how to invest with the cards we are dealt.