Authored by He Huifeng via The South China Morning Post,

In an inglorious echo of 2007 America, many young homeowners in booming cities owe more than they earn, and some even falsify salary details to get bigger mortgages...

Young Chinese like Eli Mai, a sales manager in Guangzhou, and Wendy Wang, an executive in Shenzhen, are borrowing as much money as possible to buy boomtown flats even though they cannot afford the repayments.

Behind the dream of property ownership they share with many like-minded friends lies an uninterrupted housing price rally in major Chinese cities that dates back to former premier Zhu Rongji’s privatisation of urban housing in the late 1990s.

Rapid urbanisation, combined with unprecedented monetary easing in the past decade, has resulted in runaway property inflation in cities like Shenzhen, where home prices in many projects have doubled or even tripled in the past two years.

City residents in their 20s and 30s view property as a one-way bet because they’ve never known prices to drop. At the same time, property inflation has seen the real purchasing power of their money rapidly diminish.

“Almost all my friends born since the 1980s and 1990s are racing to buy homes, while those who already have one are planning to buy a second,” Mai, 33, said.

“Very few can be at ease when seeing rents and home prices rise so strongly, and they will continue to rise in a scary way.”

The rush of millions young middle-class Chinese like Mai into the property market has created a hysteria that eerily resembles the housing crisis that struck the United States a decade ago. Thanks to the easy credit that has spurred the housing boom, many young Chinese have abandoned the frugal traditions of earlier generations and now lead a lifestyle beyond their financial means.

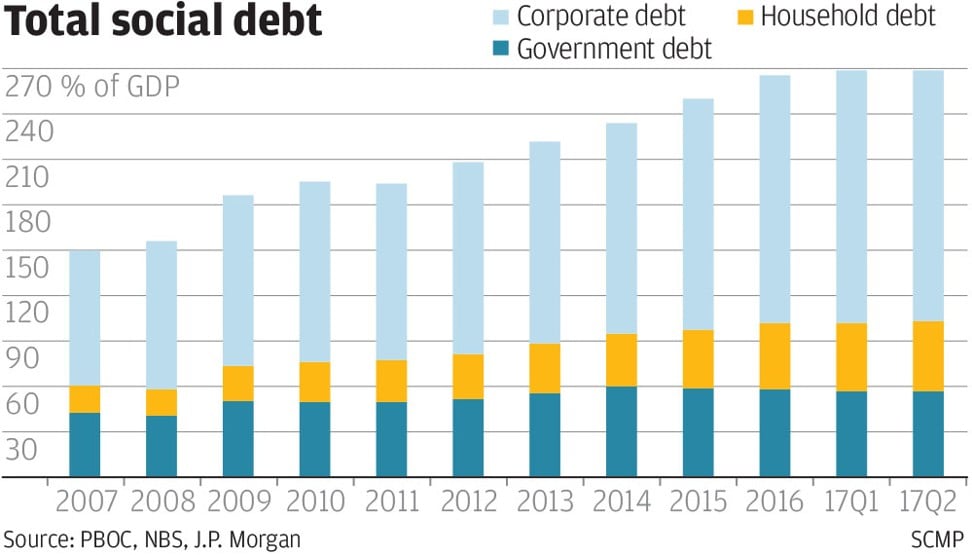

The build-up of household and other debt in China has also sparked widespread concern about the health of the world’s second largest economy.

The Chinese leadership headed by President Xi Jinping has taken a note of the problem and launched an unprecedented campaign in the second half of last year to curb home price rises in major cities by raising down payment requirements, disqualifying some buyers and squeezing the bank credit available for home buyers. The campaign is still deepening, with five more cities introducing rules last weekend that will freeze some property deals.

Meanwhile, China’s financial regulators have launched an investigation of “consumer loans” in big cities because a torrent of consumer credit flowed into the property market after the government imposed restrictions on mortgage loans.

Government policies are also protecting the interests of homeowners. City governments have squeezed land supply to keep land prices high and made secondary market trading less attractive, with new home buyers left to compete for a few new developments. Meanwhile, there is no property tax, which encourages homeowners to hold on to appreciating property assets.

The result has been skyrocketing housing prices in Shenzhen, Beijing and Shanghai, where property prices can match those in Hong Kong or London.

The lesson was that “if you don’t buy a flat today, you will never be able to afford it”, Wang, 29, said.

Property ownership was now increasingly what separated the rich and the poor, the haves and have-nots, and the privileged and the underdogs, she said.

And that means young people like Mai and Wang are scrambling for credit to buy property.

In May last year, after the value of his first flat, a 70 square metre unit in Guangzhou’s Panyu subdistrict, soared from 900,000 yuan (US$136,500) to 1.2 million yuan in just a few months, Mai, who has a monthly salary of 15,000 yuan, decided to raise the down payment for a new property to cash in on the booming housing market.

In June, he emptied his and his parents’ 300,000 yuan in savings and incurred debts to friends to muster the 50 per cent down payment for a 2.4 million yuan flat.

To meet the mortgage repayments of about 12,000 yuan a month on the two flats, and other debts to friends, he used the first flat as collateral for a loan about 800,000 yuan and got 200,000 yuan in cash from a short-term consumer loans supposedly for a car.

Mai got the money easily from local banks and financial institutions. Now, he needs to pay about 25,000 yuan a month for loans totalling around 3 million yuan, including around 4,000 yuan in mortgage payments for his first flat, about 7,300 yuan in mortgage payments for his second flat, nearly 9,000 yuan on the secondary mortgage for his first flat, 3,800 yuan for car loans, and the rest to service debts to family members and friends.

In Wang’s case, she borrowed 500,000 yuan from her parents, relatives and friends and sourced another 300,000 yuan from credit cards and consumer loans to pull together 800,000 yuan late last year for the minimum down payment on a small flat.

She also borrowed 1.8 million yuan from a bank, with monthly mortgage payments of about 9,600 yuan – 80 per cent of her monthly income – for 30 years. To help cover the mortgage, her mother, a retiree who lives 4,000km away in a city in northeastern China, remits the bulk of her pension to Wang.

“The debts are huge to me,” Wang said. “But a person without a flat has no future in Shenzhen.”

In China’s world of debt, household debt is supposed to be much safer than corporate or local government debt. Outstanding household loans were the equivalent of 44.4 per cent of China’s gross domestic output last year, more than double the ratio in 2008 but much lower than in most advanced economies. The ratio is 87 per cent in Britain, 79 per cent in the United States and 62 per cent in Japan.

But the figure could be misleading because it failed to reflect regional differences and it under-reported many hidden family debts in China, a recent report by the Institute for Advanced Research at Shanghai University of Finance and Economics said.

Because Chinese household incomes were growing more slowly than property prices, families were facing serious liquidity problems, with increasing amounts of income and savings sucked into the property market, Chen Yuanyuan, a co-author of the report, told the South China Morning Post.

Real household debt would have been the equivalent of at least 60 per cent of China’s GDP at the end of last year, Chen said, warning that the rapid rise in household debt was undermining China’s economic growth prospects.

China’s crackdown on grey rhinos won’t reduce its debt burden, it will only redistribute it

“If it goes on, as early as in 2020, the ratio of mortgage debt and disposable income in China will reach the same peak level [127 per cent] as the US [in 2007] on the eve of the subprime crisis,” Chen said.

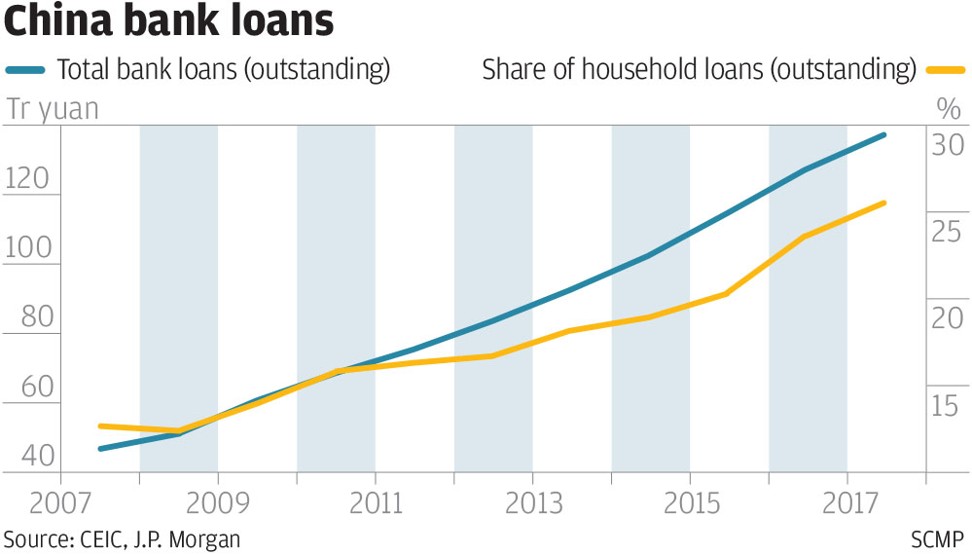

The boom in China’s housing market since 2015 was the result of soaring household debt leverage, Jiang Chao, an analyst at Haitong Securities in Shanghai, said in a research note last month.

China’s household debt to household disposable income ratio had soared to 90 per cent from less than 35 per cent in 2007, he said. Meanwhile, its household savings to household disposable income ratio had dropped from more than 30 per cent in the early 2000s to about 15 per cent last year.

The latest data from the People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank, shows that at the end of May, domestic household savings deposits totalled around 63 trillion yuan while the amount of outstanding personal loans had soared to 36.4 trillion yuan, up from 8.8 trillion yuan in 2010.

The Chinese tradition of saving money for a rainy day has been uprooted, and it’s not just that the younger generation, like Wang and Mai, are trying to spend before they earn. Their property buying frenzy has also been endorsed by their parents.

“My mum is happy about my decision,” Wang said.

Shenzhen is one of the most indebted cities in China. Data from Lianjia, the country’s biggest property agent, shows that Shenzhen property buyers took on a record amount of debt last year, with mortgage loans a feature of more than 93 per cent of purchases.

Property buyers in the city spent an average of about 3.7 million yuan on their flat in the first half of last year, with mortgage loans averaging 2.38 million yuan, Lianjia said, resulting in an average loan-to-value ratio of just over 64 per cent. In Hong Kong, banks’ average loan-to-value ratio for new mortgages was 51 per cent in December, according to Standard & Poor’s, while in the US last year it was 55.5 per cent, according to Statista, a leading Web-based data and statistics provider.

China’s first home buyers are, on average, younger than those elsewhere in the world, with most of those in Shenzhen in their 20s and 30s. On average, they need to pay about 10,600 yuan a month for 30 years for their first flat – or 13,000 yuan for 20 years – based on the current mortgage interest rate of 4.9 per cent. Meanwhile, the average white-collar salary in Shenzhen was 8,315 yuan last year and 8,892 yuan in the first quarter of this year, according to Zhaopin.com, a leading Chinese jobs website.

“Chinese banks typically allow homebuyers to use up to half of their monthly incomes to repay mortgages,” said Julia Fan, a former state bank manager.

“But the market in cities like Shenzhen and Shanghai is full of buyers whose out-of-pocket property spending is much more than their actual monthly salaries.”

Bill Duan, a manager at a Chinese investment bank, said it was not unknown for Chinese buyers to exaggerate their salaries or use fake payslips when taking out mortgages and loans, “and this may be when the problem starts”.

“It’s known among industry insiders that local branches of the banks in many cities do not always double-check salary details with employers, even though the applicants offered salary certificates for several times the city’s average wages,” he said.

Mai and Wang have been playing it fast and loose to deal with their debts.

Mai has lent 600,000 of the 800,000 yuan he got from a bank after using his first flat as collateral to a money shark promising an annualised return of 20 per cent. Wang gave the bank fake documents showing her monthly income was 18,000 yuan – about 1.6 times her actual salary. It did not ask any questions.

Neither see any problem, because the value of their underlying assets, the flats, have risen.

The value of Mai’s two flats rose from 3.8 million yuan last year to 6.4 million yuan last month, while the value of Wang’s unit is now 2.93 million yuan, up from 2.6 million yuan.

“I think I made a smart and successful decision to leverage debt,” Mai said.