Submitted by Charles Hugh-Smith of OfTwoMinds blog,

The upper middle class is well and truly doomed by self-delusion and the pathology of entitlement.

Two recent articles describe America's entitled (and doomed) upper middle class: the top 5% of households with incomes above $206,500 annually and individuals with incomes of $160,000 or higher annually. (source: Historical Income Tables: Households Census.gov)

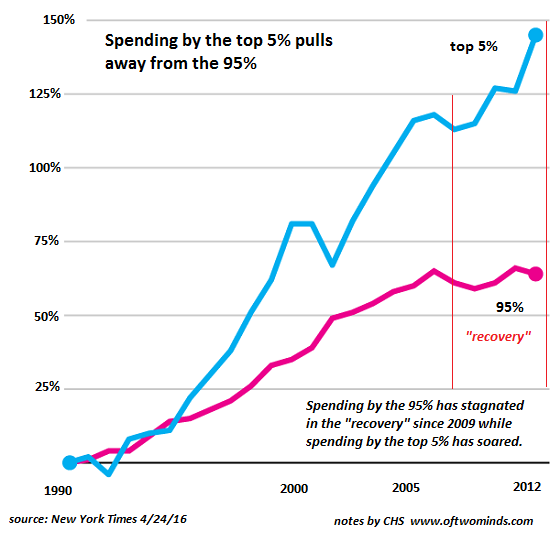

The first describes how businesses are responding to the new Gilded Age in which spending by the top 5% has pulled away from the stagnating bottom 95%:

In an Age of Privilege, Not Everyone Is in the Same Boat Companies are becoming adept at identifying wealthy customers and marketing to them, creating a money-based caste system.

With disparities in wealth greater than at any time since the Gilded Age, the gap is widening between the highly affluent — who find themselves behind the velvet ropes of today’s economy — and everyone else.

The Haven’s 95 staterooms were located so high up in the forward part of the ship that even guests in comparatively expensive staterooms might remain unaware of its existence. Depending on the season, a room in the Haven might cost a couple $10,000 for a weeklong cruise vs. $3,000 for an ordinary stateroom elsewhere on the ship.

Since the late 1990s, however, “there has been a huge evolution, maybe a revolution in attitudes,” Mr. Goldstein said. In addition to larger rooms or softer sheets, big spenders want to be coddled nowadays. “They are looking for constant validation that they are a higher-value customer,” he said. For example, room service requests from Royal Suite occupants are automatically routed to a number different from the one used by regular passengers, who get slower, less personalized service.

With a week in a top Royal Suite costing upward of $30,000, compared with $4,000 for an ordinary cabin, the focus is on “very affluent travelers, and we have no trouble filling these rooms,” Mr. Bayley said.

The second article is by an upper middle class writer who bemoans his declining income and status:

The Secret Shame of Middle-Class Americans: Nearly half of Americans would have trouble finding $400 to pay for an emergency. I’m one of them.

We are naturally sympathetic to anyone describing themselves as middle-class who is in such dire financial straits that they don't even have $500 as an emergency fund.

But as we read further, we find the author is hardly a typical middle-class worker-bee: he was a substitute host on a national television program for a few years, received substantial advances for books he wrote (substantial enough for him to complain about the taxes due), got a Hollywood movie deal for another book he wrote, etc.

He was making enough money to suggest his film-producer spouse (yet another not-a-middle-class job) quit working, and to buy a house in the tony Hamptons which he poo-poos as nothing special. (A home in a pricey premier suburb is nothing special? In what circles is it nothing special?)

The solution to his poverty is obvious to the rest of us: sell his Hamptons home and moving to less tony digs. He could buy a house in a Midwest college town for a fraction of the Hamptons house and live happily ever after off the cashed-out equity.

The writer was never middle-class--he was upper middle-class, with upper middle-class income, assets and aspirations.

Then come his complaints: he made too much money for his kids to get financial aid to Stanford (fire up the sad violins of sympathy), so his parents had to pony up the $150,000 for each kid to attend an Ivy league university--oh, and then go on to earn Masters degrees or higher.

His wife, out of the work force for the years he was raking in big bucks, couldn't find a job as a film producer (how awful!)--and then she vanishes from the narrative: did she lower herself to take a "normal" job, or is she still a Hamptons Housewife? Are we not being told because it doesn't fit the "poor me" narrative?

His 401K retirement was sacrificed to pay for one of his daughter's wedding--and how much did that extravganza cost? Was that a wise decision?

The writer confesses he's made poor financial decisions, but he lays the blame on economic ignorance rather than the real cause: his overwhelming sense of entitlement.

This is not simply hubris; it is a pathology that characterizes America's upper middle-class, and those who aspire to membership in that class.

This article expresses the core belief of America's upper middle class: I deserve to make more money every year until I decide to retire. Then I deserve a well-funded retirement in an upper middle-class neighborhood with all the usual upper middle-class trimmings.

The list of entitlements is practically endless: my wife shouldn't have to work, even though writers' incomes are notoriously uneven; my daughters deserve to attend Ivy league colleges without taking on $100,000+ in student loan debt; they deserve lavish weddings that they don't have to pay for; I deserve a recent-vintage auto, numerous nights out to movies and dinner, annual vacations (we can assume overseas vacations, of course; how gauche to travel only in the U.S.), and so on--an endless profusion of entitlements that are completely unmoored from the realities of their chosen careers in writing (insecure) and film production (insecure).

Memo to the author: did you somehow not notice that the money to pay writers is drying up? Did you not notice that book advances are vanishing like rain in Death Valley? How clueless does a writer have to be not to be aware of the structural changes in his industry?

The writer sets out to illuminate the precariousness of middle-class life, using himself as an example: a high-end New York writer/author and his equally high-end New York film producer spouse, who made tons more money than the $50,000-per-year middle class household and managed to buy a home in one of the most desirable suburbs in America.

The writer is aware of the disconnect, and he attempts to mask this by downplaying his previous (high) income and the value of his Hamptons home. (I got the feeling he didn't even want to disclose he owned a home in the Hamptons.)

Given prices in the area, the writer is sitting on hundreds of thousands of dollars in equity--and if he had drained the equity, we can be sure he would have disclosed this poor-me factoid.

Is this a household that is flat-broke, or a house-rich, cash-poor household that spent far beyond its means for years in the belief that the upper middle-class were magically entitled to a high income, regardless of economic realities?

As we look at the economic landscape, we find this class the fantastically entitled bourgeois dominating the technocrat / managerial / professional layers of our economy--the people who pen the editorials and edit the news reports, the people with tenure or high-paying government jobs--the people who claim the mantle of knowing what's what.

The reality is this class of entitled bourgeois is utterly clueless about the financial realities that are about to hit the global economy like a tidal wave. The top 5% aren't prepared to weather a mild storm, much less survive a tsunami. They are well and truly doomed by their self-delusion and their pathology of entitlement.

With this clueless class in positions of leadership, where does that leave the nation?

Meanwhile, the economic realities that the top 5% have evaded (thanks to the "recovery" that benefits the few at the expense of the many) have pushed U.S. Suicide Rate to a 30-Year High.