Authored by James Rickards via The Daily Reckoning,

Market crashes often happen not when everyone is worried about them, but when no one is worried about them.

Complacency and overconfidence are good leading indicators of an overvalued market set for a correction or worse. Prominent magazine covers are notorious for declaring a boundless bull market right at the top just before a crash or correction.

October 19 saw the thirtieth anniversary of the greatest one-day percentage stock market crash in U.S. history - a 22% fall on October 19, 1987. In today’s Dow points, a 22% decline would equal a one-day drop of over 5,000 points!

I remember October 19, 1987 well. I was chief credit officer of a major government bond dealer. We didn’t have the internet back then, but we did have trading screens with live quotes. I couldn’t believe what I was watching at first, but by 2:00 in the afternoon we were all glued to our screens.

It was like being a passenger on a plane that was crashing, but you had no way out of the plane. Our firm was fine (bonds rallied as stocks crashed), but we were concerned about counterparties going bankrupt and not being able to pay us on our winning bets in bonds.

What’s troubling is that a lot of commentators said that the kind of crash that took place in 1987 couldn’t happen today and that markets were much safer. It’s true that circuit breakers and market closures could temporarily halt a slide better than we did in 1987. But those devices buy time, they don’t solve the underlying fear and panic that causes market crashes.

In any case, when I hear market pros say “It can’t happen again” it sounds to me like another market crash is just around the corner.

The problem with a market meltdown in today’s even more deeply interconnected markets, is that once it strikes, it’s difficult to contain. It can spread rapidly. Likewise, there’s no guarantee that a stock market meltdown will be contained to stocks.

Panic can quickly spread to bonds, emerging markets, and currencies in a general liquidity crisis as happened in 2008.

Why should investors be so concerned right now?

For almost a year, one of the most profitable trading strategies has been to sell volatility. That’s about to change…

Since the election of Donald Trump stocks have been a one-way bet. They almost always go up, and have hit record highs day after day. The strategy of selling volatility has been so profitable that promoters tout it to investors as a source of “steady, low-risk income.”

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Yes, sellers of volatility have made steady profits the past year. But the strategy is extremely risky and you could lose all of your profits in a single bad day.

Think of this strategy as betting your life’s savings on red at a roulette table. If the wheel comes up red, you double your money. But if you keep playing eventually the wheel will come up black and you’ll lose everything.

That’s what it’s like to sell volatility. It feels good for a while, but eventually a black swan appears like the black number on the roulette wheel, and the sellers get wiped out. I focus on the shocks and unexpected events that others don’t see.

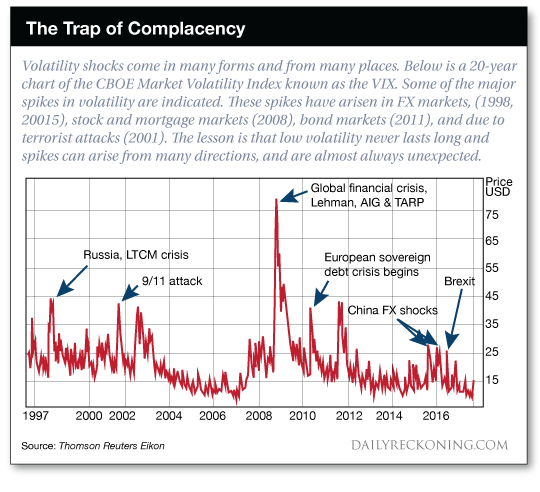

The chart below shows a 20-year history of volatility spikes. You can observe long periods of relatively low volatility such as 2004 to 2007, and 2013 to mid-2015, but these are inevitably followed by volatility super-spikes.

During these super-spikes the sellers of volatility are crushed, sometimes to the point of bankruptcy because they can’t cover their bets.

The period from mid-2015 to late 2016 saw some brief volatility spikes associated with the Chinese devaluation (August and December 2015), Brexit (June 23, 2016) and the election of Donald Trump (Nov. 8, 2016). But, none of these spikes reached the super-spike levels of 2008 – 2012.

In short, we have been on a volatility holiday. Volatility is historically low and has remained so for an unusually long period of time. The sellers of volatility have been collecting “steady income,” yet this is really just a winning streak at the volatility casino.

I expect the wheel of fortune to turn and for luck to run out for the sellers.

Here are the key volatility drivers we should be most concerned about:

The North Korean nuclear crisis is simply not going away. In fact, it seems to be getting worse. Intelligence indicates that North Korea successfully tested a hydrogen bomb in September. This is a major development.

An atomic weapon has to hit the target to destroy it. A hydrogen bomb just has to come close. This means than North Korea can pose an existential threat to U.S. cities even if its missile guidance systems are not quite perfected. Close is good enough.

A hydrogen bomb also gives North Korea the ability to unleash an electromagnetic pulse (EMP). In this scenario, the hydrogen bomb does not even strike the earth; it is detonated near the edge of space. The resulting electromagnetic wave from the release of energy could knock out the entire U.S. power grid.

Trump will not allow that to happen, and you can expect a U.S. attack, maybe early next year.

Another ticking time bomb for a volatility spike is Washington, DC dysfunction, and the potential for a government shutdown in December…

Analysts who warn about government shutdowns are often viewed as the boy who cried wolf. We’ve had a few government shutdowns in recent years, most recently in 2013, and two in the 1990s.

These were considered true government shutdowns in the sense that Congress did not authorize spending for any agency, and all “non-essential” government employees were put on furlough. (Critical functions such as military, TSA, postal service and air traffic control continue regardless of any shutdown).

These shutdowns don’t last long. They are usually for one political party or the other to make its point about spending priorities, and are soon compromised in the form of higher spending and a return to business as usual.

Government shutdowns because of lack of spending authority are different from government shutdowns due to lack of borrowing authority and the Treasury’s inability to pay its bills, or hitting the so-called “debt ceiling.”

We had a debt ceiling shutdown in 2011. Those are far more dangerous to markets because they call into question the Treasury’s ability to pay the national debt. We’ve had two near shutdowns this year; one in March, and again at the end of September. Both times Congress passed a last minute “continuing resolution” or CR that keeps government funding at current levels and keeps the doors open until a final budget can be worked out.

The current CR expires on December 8.

This time the odds are high that the government actually will shut down. Why should investors be any more concerned about this shutdown than the one in 2013 or the near misses earlier this year?

There are several causes for concern.

The first is that there is less room for compromise. The White House wants funding for the Wall with Mexico. Many Republican members of Congress want to defund Planned Parenthood. The Democrats will not vote for the Wall or to defund Planned Parenthood, but do want more funding for Obamacare.

There is no middle ground on any of these issues so the chance of a long shutdown is quite high.

The second reason is that this shutdown comes at a time when the U.S. in facing an increased risk of war with North Korea, and Congress has many other tasks on its plate including tax reform, confirmation of a new Fed Chairman, the “Dreamers” legislation, and more. Political dysfunction in Washington can easily spill over into markets.

This time the wolf may be real.

In short, the catalysts for a volatility spike are all in place. We could even get a record super-spike in volatility if several of these catalysts converge.

The “risk on / risk off” dynamic that has dominated most markets since 2013 is coming to an end. From now on it may just be “risk off” without much relief. The illusion of low volatility, ample liquidity, and ever rising stock prices is over.

It has been nine years since the last financial panic so a new one tomorrow should come as no surprise.

The safe havens will be the euro, cash, gold and low-debt emerging markets such as Russia. The areas to avoid are U.S. stocks, China, South Korea and heavily indebted emerging markets.

It may not look like it now, but it could be a volatile and bumpy ride ahead.