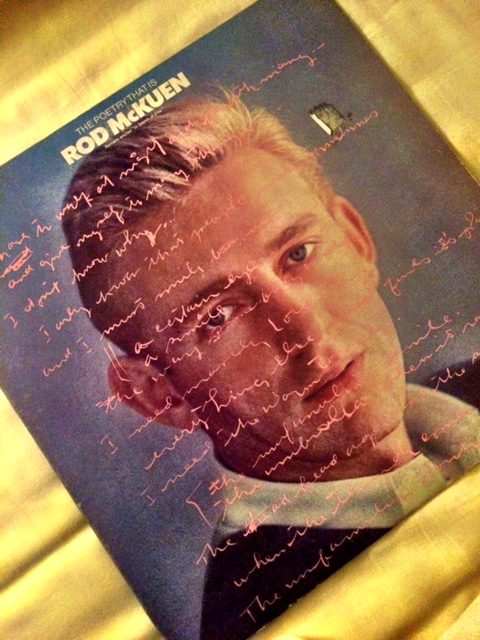

Photo by Rod Dreher

When I pulled back the covers last night, this was lying in my bed, not un-horse-headishly. It had been placed there by my elder son, who picked it up at on thrift store run.

There will be payback. Let the word go forth.

But I am genuinely grateful for this prank for one reason: it led me to Carlos Cunha’s appreciation of McKuen, published in the LA Review of Books shortly after the poet’s death last year. As someone for whom Rod McKuen has always been the epitome of the shag-carpet excess and shmaltz of the 1960s and 1970s, this essay made an impression on me. Cunha, as a young man in South Africa, fell in love with McKuen’s verse, and though he later came to understand its, er, limits, he respects McKuen’s achievement. Excerpt:

But McKuen, I believe, does not properly belong to the literary world, so why submit him to its judgment? His poetry is not erudite poetry, not literary poetry. It is pop poetry, which is a genre that, in its written form, has become practically extinct, with McKuen having been its last major exponent. At least in English-speaking countries, the place of pop poetry has been entirely taken over by the song or rap lyric, which depends for its charm less on its words (which are often unquestionably illiterate and artless) than on the musical accompaniment, the fashion, the stagecraft, the video, and other infantile razzle-dazzle. McKuen may not lay claim to any genuine literary achievement, but he could make a few words on a bare page seem at least as enchanting to a teenager as a good rock ballad. And the literary standards of those poems were certainly higher than most of the pop song lyrics that directly competed with him for the memories and mimicry of the youth of my time. And many of his young fans grew up to be writers themselves: I have never met another McKuen man or woman who was not also still involved with the written word somehow. McKuen not only helped a lot of people fall in love with others, he helped a lot of people fall in love with writing.

That McKuen sold millions of books worldwide, something no poet since has been able to do, is by itself a startling marker in cultural history, much worthier of consideration and analysis than of condescension and vitriol. McKuen was a valid, global phenomenon of pop culture who deserved, in his obits, a sympathetic reassessment rather than a harsh rehash of the hasty dismissals of his time. But perhaps Kevin Blackie or some documentarian like Rodriguez’s is even now priming his iPhone to put together a film that will do that Great American Loner a bit more justice. Too bad it didn’t happen, as in Rodriguez’s case, while the man was still alive.